VISUAL DOCUMENTARY

PROJECT 2015

Human Flows -Movement in Southeast Asia

Documentary Line-up

Humanosphere »

VISUAL DOCUMENTARY PROJECT 2015

Human Flows

Movement in Southeast Asia

Humanosphere »

VISUAL DOCUMENTARY PROJECT 2015

Human Flows

Movement in Southeast Asia

Humanosphere »

VISUAL DOCUMENTARY PROJECT 2015

Human Flows

Movement in Southeast Asia

Humanosphere »

Applications: Closed

Deadline for submission: December 20, 2015

About the Project

Southeast Asia is rich in its diversity of ethnic, religious and cultural composition. The region has maintained the coexistence of such diversity while at the same time achieving economic progress and becoming a hub for the flow of people, goods, money and information. Yet at present, the region is also confronted with serious issues such as the decrease of biodiversity and tropical forests, disasters, pandemics, aging population, ethnic and religious conflicts, economic differentiation and poverty.

In the face of this, how is coexistence and sustainability possible despite the diversity that exists? How can we make public resources out of the region’ s social foundations which are the basis of people’ s everyday lives? And, how can we connect these in a complementary way to existing systems of governance towards solving the problems and issues mentioned above?

In order to address these questions in the context of Southeast Asia, the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University has initiated this “Visual Documentary project” which explicitly examines the contours of their everyday lives through a visual approach since 2012. This project aims to use visual forms of expression to complement the growing literature that exists on Southeast Asian societies. From 2014, the Japan Foundation Asia Center joins this project as co-organizer to help widely promote the richness of Southeast Asian cultures to people in Japan. As of 2015, the project has linked up with numerous film schools in the region to help strengthen the documentary filmmaking network.

http://www-archive.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/sea-sh/en/documentary_project_top/

Organized by Center for Southeast Asia Studies, Kyoto University and The Japan Foundation Asia Center

In cooperation with Yangon Film School, Documentary Arts Asia, WATHANN FILM FESTIVAL, In-Docs, Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center

Human Flows

- Movement in Southeast Asia -

Movement is a fundamental reality of human societies. In Southeast Asia how does it influence individuals, families, communities and nations? What journeys do people take as they move within, across and out of the region? What are their reasons to move and what stories do they have to tell? What experiences define movement in the region? And how will the region’s governments manage flows on the eve of the birth of ASEAN Economic Community?

The Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS) is accepting short documentaries from young filmmakers who are citizens of Southeast Asian nations and Japan to reflect on Human Flows in Southeast Asia. Submissions of up to 30 minutes can be on any topic that touches upon Southeast Asian’s experiences of human movement in the region. Themes can include economic migration, movement between countries in the region, pilgrimages, migration due to political crisis or environmental degradation, cultural influences and borderless journeys/wanderings.

“The Social Significance of Documentaries” by Rithy Panh

PART1 LECTURE PART2 Q&A SESSION

Rithy Panh, the oscar nominated Cambodian documentary filmmaker, came to CSEAS to screen “S21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine” (2003) and talk about the social significance of documentaries.

Date: Tuesday June 9th

Venue: Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Inamori Memorial 3rd floor, Large Meeting Hall

Film screening: “S21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine”

Lecture: “Social Significance of Documentaries: How Can Documentary Film Depict and Communicate the Memories of Massacre”

Q&A Moderator: Satoru Kobayashi (CSEAS)

Film Screening and Lecture by Rithy Panh: Part1 Lecture

Hello everyone. First of all, I would like to express my appreciation for the Center of Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University and the Japan Foundation Asia Center. It is indeed, a privileged moment for me to meet you on this occasion. I would like to say thank you from the bottom of my heart for you all being here today.

Hello everyone. First of all, I would like to express my appreciation for the Center of Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University and the Japan Foundation Asia Center. It is indeed, a privileged moment for me to meet you on this occasion. I would like to say thank you from the bottom of my heart for you all being here today.

I am a filmmaker and my regular job is to make films and not to deliver speeches in front of people. However, I would like to express my own opinion on the proposed theme today, a very important one. The theme is the power of documentary, its role in documenting genocide, the crime of genocide itself, and its memory.

First, with regard to the crime of genocide, in the case of Cambodia, about 1.8million people are said to have been slaughtered. The number is equivalent to one fourth the population back at that time. What is significant about the number 1.8 million? There is probably a difference between the crime of genocide, that is, crimes against humanity and regular crimes that take place in any part of any city.

For me, this number means 1.8 million lives; 1.8 million individual histories; 1.8 million faces; and 1.8million names. When we talk about the facts of the massacre in this way, we would frequently mention such numbers, but we hardly talk about the respective fate of each individual hidden behind the numbers.

We feel as if we know everything, but as a matter of fact, we know nothing. That makes things more complicated. In fact, in the wake of such a genocide, issues as how to reestablish the nation, build social organizations, and create national history and the collective memory of the nation have to be raised.

Beyond such matters of the dead, what I am interested in is the fact that there existed the will to carry out the massacre and that there existed the intent to carry out genocide. For if there had been no such intent, the genocide would never have taken place. If they (the perpetrators) had no such will, it would be impossible to explain what it was; a form of collective insanity or something else? When thinking about genocide, you must prove that there existed the intention to commit it.

Genocide is the attempt to kill or eliminate other people. It is more than just the eradication of their physical bodies; it aims to eliminate their identities as well.

In the language of the Khmer Rouge, the word “killing” or “executing” was substituted by a peculiar term “Kamtech.” This term means to destroy, to reduce to dust, or to crush and it is much more eloquent than the simple word, “killing.”

To work for the sake of memory is to give identities back to the people who vanished. It is to provide them with their names and faces. Then, we can discuss history. It is the individual history and our history, the history of us as a group, my history as well as yours. That is why my first important task in Cambodia was documentation. Then the work can go beyond the history of the Khmer Rouge and proceed further.

We have to retrieve our history that existed before the time of the Khmer Rouge, as our past is very much connected to our present. This task resembles building a bridge over a huge empty hole called genocide. This is the work that relates to genocide. If anything I do can be called a success, it will be that I gave back a few names to a few faces over the last 20 years. Yet, a few persons in two decades are not so many.

My work has been a long and difficult task however, since it was my history. I have had to face it. I could have been satisfied with keeping silence. I respect the opinion of those who would say they don’t want to make any more comments. Because I myself cannot be sure, whether speaking could make me feel better or not.

However, it is harder for me to keep silence and not make remarks than to speak. This is because the survivors like us survived the tragic genocide, not because we were stronger or more courageous than others.

We survived partly because other people helped us. Thus, we come back full circle. In a sense, the work of documentary on genocide was to question who were the other people and who were the vanished people? Whatever way I try to do it, I cannot get out of answering this question. I cannot run away from this history. That is why I have to encourage myself to give names back again to those who had helped me, those to whom I owe my survival.

Despite this, I’m working on this task with great hope. It is my hope that someday, sometime, at some point, all these efforts will be successfully accomplished. It is also my hope that the same history will not repeat itself. Though, of course, I am aware that history has actually repeated itself many times over.

This is like a struggle between good and evil. Evil is always more powerful than good. The work of fighting against evil and those working for the sake of memory are always on the side of the weak. In the struggle, we are always the losers. But we must wage our struggle as that alone can bestow dignity on human beings. People cannot live without dignity.

The movie you have just seen, “S21 the Khmer Rouge Killing Machine,” was filmed at S21, which used to be a prison and an execution ground of the Khmer Rouge. It is located in central Phnom Penh.

There are various execution grounds all over the nation and people often ask me why I have chosen S21. In fact, when I visited S21 for the first time, I just couldn’t make myself enter there. Though I brought myself to the front of the gate, I just couldn’t go through the gate to step inside the ground.

However, I had a strong wish to enter there. I was hoping to enter the place to find a trace of my uncle, who had been executed in S21. Yet, I felt as if the very act of entering the place to look inside the execution ground was something vulgar. Gradually, I came to see the importance of thinking about the killing machine at the core of the authority of the Khmer Rouge.

Understanding S21 also means to understand the regime of Khmer Rouge. It is important to understand S21. However, if you just pay attention to the number of the people killed there, as it amounts to a little less than 13,000, S21 is merely ranked at 12th or 13th among other execution grounds as far as the number of the executed is concerned. However, S21 was something special to me. S21 seemed like the state among all states for me. Besides, some scholars told me that S21 had actually been used by the Khmer Rouge as a site to purge and kill their own members. The reality was much more complicated than this.

Many executive members of the Khmer Rouge were executed in S21. Yet, a lot of intellectuals, children and women were also slain there. Some were killed outside of S21, due to what had been done in S21. This is because S21 was a place in which they used to make the list of people to be arrested, executed, and eliminated. Then, it was important to see it clearly, how mechanically the bloodshed had been conducted. How could they create such a dreadful atmosphere in S21?

And what kind of vocabulary was used in S21? In fact, there were various issues that presented themselves and we needed to approach them like archaeologists. Like an archaeologist studying the ruins of a temple, I tried to sift and uncover the various layers that had accumulated, one by one, in S21. From one layer to another, from one point to another, we conducted our research and dug down. We repeated the process of this research and exploration.

There is much historical research done on S21 and there are political studies, but there are no anthropological studies. For me, things were more complicated. As you might probably know, I am a film maker, and from the very moment I bring my camera into a crime scene like S21, I will be sharply aware of the moral and ethical issues. Because there is a possibility that those images can instantly gain some vulgarity or voyeuristic taste. Cinematically, my work has been interesting too. It was also a way to think how we use our camera to make it a tool to reassemble memories.

Films are obviously something subjective. And I accept the subjectivity as my own. The same is true of memories. Memories are something unfixed and they keep on changing, evolving and transforming. Therefore, it was necessary for the documentary work, the visual work to find it’s proper position or it’s own space in the place called S21.

I have also noticed that physical memories were important for me. They were more important than verbal or visual memories and they existed there as something explicit that I thought I could record to turn them into images.

As you will have seen in the movie, there was perhaps a surprising scene. It was the one of a former guard re-enacting the movements he used to do in those days. Various people often ask me how he could act in that way. But he was not acting. He is not an actor.

He did not repeat or reproduce what he remembered. Neither did I direct him. In fact, there are only two people who can perform these movements. One is the prisoner, but since they were all slaughtered, he cannot re-enact their movements. The other person who can perform those movements is the slaughterer. It is impossible for me to know the chronological sequence of those motions.

There is a particular sequence for the motions and they cannot be performed at random. In terms of capturing such physical memories, memories of the body, the film project became an interesting one.

As with either of the cases of the Jewish Holocaust or Cambodian genocide, there were many survivors. They were wounded yet even if their scars have already healed, they still feel the pain of their wounds from 30 years ago. The same is true for the slaughterer. The violent motions, that is to say, his internal violence, flashes back as his unconscious memories and that moment can be captured by the camera. That was one of the important points I wanted to expand in my film when scrutinizing the function of S21.

To be exact, there is one more thing that needs to be mentioned: It was not my idea to set up such a confrontation between the victims and the slaughterers. It was triggered by an accidental meeting a few years before the film-shooting of “S21.”

At that time, I was shooting another movie titled “Bophana: A Cambodian Tragedy.” During the shooting, I felt like interviewing one of the people on the slaughterer’s side.

A painter Van Nath, who appears in “S21” is a survivor and I didn’t want him to meet a slaughterer. So the shootings were held separately. I was thinking that I didn’t have the right to let or force victims to meet someone on the slaughterers’ side. So, we always recorded the people on the slaughterers side outside of S21 in a separate place. And the interviews with the painter Van Nath were held inside of S21.

One day, it started raining when I was doing a recording with a slaughterer. So, I decided to continue the shooting inside S21. I thought it was fine, because it was raining. Then, I asked one of my assistant directors to go and inform Van Nath not to come, as we were shooting inside the building.

Next day, we started the work with Houy, the former chief of the guards at S21. It was probably around 10 or 11 in the morning and we noticed Van Nath coming to S21. I was anxious because there might be some trouble between them, however, Van Nath was very calm and seemed to observe Houy for half an hour or so. Then, he approached him and started to talk to him. To my surprise, he put his hand on Houy’s shoulder and led him to see his paintings of S21. In his paintings, Van Nath was depicting what kind of crimes had taken place at S21. He showed his works to the former guard and provided him with explanations.

Van Nath portrayed in his paintings the crimes that had been carried out in S21. He asked Houy about each piece of his paintings, if they were really like that or if they were correct. For instance, he asked Houy as follows: “I didn’t see the scene with my own eyes, but I painted this one according to what I’ve heard, isn’t it too exaggerated?” Then, each time he asked, Houy would reply “Yes, it was surely like that,” “Yes, it really happened in that way.” Indeed, a great process of memory was taking place before my eyes.

Later, I read a passage from a book by Primo Levi, “Survival in Auschwitz: If This Is a Man.” There was a strong fear for Primo Levi on the way back from a Nazi concentration camp to his own home in Italy. It was the fear that nobody might believe his story about what he had experienced there.

Then, I finally realized there, the meaning of the painter’s behavior. He brought the chief guard of the Khmer Rouge and was confirming with him what had really been taking place in S21.Van Nath was exquisitely tackling the work of memory concerning S21 through his paintings. They are brilliant works, but as paintings, they are subjective. He offered testimony from the victim’s side but one-sided evidence is not sufficient. We also need testimony from the perpetrator’s side.

As you see, movies are something very odd. It was not me who decided to set up the confrontation or the encounter between the victims and the perpetrators, but the confrontation between the two just came to me by itself as if it was something significant and inevitable. If I had been the one who had set it up, it would have ended up as a disappointing result because that would be something just staged.

That kind of moment is perhaps the only reason why I remain attached to documentary films. There is always something human about it. When you deal with such themes, you must have a conviction for documentary. That conviction is almost like a religious faith. In other words, that is a faith to believe that it is impossible to utterly destroy the human existence, that there is always a trace of memories and there is certainly evidence or a trace of memories, which can conquer temptations of utter elimination which the Khmer Rouge had intended to bring about through genocide.

I raise all of the above issues in the hope that they can be an introduction for further discussion.

Any questions will be welcomed, so please go ahead and ask me questions.

Film Screening and Lecture by Rithy Panh: Part2 Question and answer session

- Kobayashi Satoru (KS):

Thank you for your important talk. Before we move on (to the Question and answer session), I would like to say that there might be three different kinds of questions. The first kind might be about the movie “S21.” The second kind might be about the situation concerning the emergence of Cambodia at the time of Khmer Rouge, with a wider view on S21 and its background. And finally, as the title for today’s lecture is “the social significance of documentary films”, I suppose there will be some questions regarding this larger issue.

As I listened to the talk on “S21” about Cambodia during the time of the Khmer Rouge and about documentary films, I think we have been able to hear considerably about Director Rithy Panh’s opinions on these respective issues. In particular, he has talked about recognizing that the genocide meant “Kamtech,” or in short, “elimination” or “eradication existence itself.” He also stated that the biggest purpose of visualizing the genocide was to give back the names and faces to those who were eliminated and to discuss history in that sense.

We have also been provided with elaborate explanations about the detention center called S21. In the interview scene, we saw a notable encounter between Van Nath, a painter and the guards. Until today, I did not know how this encounter had come about and found it very thought-provoking.

I have here some questions collected from the audience. The first is about a specific scene in “S21.” In the film, Van Nath said to the guards “you became like an animal,” a comment which sounded like a condemnation of a kind. The questioner however, argues that animals would never torture themselves or kill each other. We received another comment claiming that the one who would carry out torture would be the human being. I would like to introduce this question as a starter. What do you (director) think about this?

Rithy Panh (RP):

I wonder if we are sure whether the one who carries out torture is a human being or ideology itself. I think we should not be pessimistic about the fate of human beings. Human beings cannot be completely good or evil. However, ideologies can sometimes bring out and stimulate the barbaric nature of human beings which is considered to be more animal-like.

At the beginning of my talk today, I used the term “intention of genocide”. With this intention, there is something we must think about. In the case of genocide, be it the Jewish holocaust or Cambodian genocide, a process of “dehumanization” is sure to take place before the massacre, through which they try to turn people into something impersonal. Thus, in that sense of turning people into something impersonal, I guess the word animal may be an appropriate expression.

Let’s say, that people were slaughtered in batches of 60 or 100 persons at one time, in the case of Cambodia, 1.8 million people were victimized and they couldn’t have killed them without this process of dehumanization. Yet, it was not only the victims who were dehumanized, but also the slaughterers themselves.

And when you try to bring back peace and restore memories, efforts should not be made only by the victims of the genocide. An effort of the memory must be made by both sides. This cannot be accomplished on ones own. The victims should not be the only ones to shoulder the burden of the task of retrieving memories.

There is also something that is quite astonishing. Ask those S21 slaughterers a simple question, “How many people did you kill?” and there will be no answer. It is not because they don’t know. It is because giving the answer is impossible for them.

Because what they had to destroy were the enemies and those enemies to be destroyed probably held no human traits for them any more. Perhaps in their eyes, even their appearance might not have been one of a human being.

From the filmmaker’s side, this was all very complicated for me. When they were sharing with us their daily routine at S21, it somewhat seemed as if there was no more meaning in life. S21 was an extremely strange world. That is to say, even if you asked them how many people they had killed, they wouldn’t reply with answers like “I killed 4” or “I killed 10”. Since there was no answer to such questions, I couldn’t continue my research in that direction.

Let me give one example. There was a scene in which I asked them a question. When I asked them “Did you often go there?” they would answer, “Yes I went there often.” Still, they couldn’t remember how many people they killed. Here is the reason; the memory of their first time killing was clear, however, when it was repeated 200 times, 1,000 times…then, the memory would not remain any more. There is no difference in saying that the 1,000 slain had no identity at all.

It is something difficult to explain, but if they killed only one person, they might remember whether the person was a man or a woman, what the name was, what the time was, or about the moment of their killing. However, when it comes to 1,000 or 10,000 persons, then, they cannot remember anything anymore and it becomes unimportant. Now, 30 years have passed but it is the same thing to say how many people were killed or to simply cite the numbers.

That is to say, when we are just referring to the number of the slain without mentioning their respective histories and names, they are not treated as human beings and thus the process of dehumanization is still at work today, weighing on us even after 30 years. That is why I think the work of documentation is very important. With Houy, he also cannot say how many people he had killed. He said by himself “as I killed for the first time, second time…and then after that, I started to feel nothing anymore,” “I could no longer sense the smell of blood”.

This is the work of eliminating people. The same was true with the case of the Rwandan genocide. Such terms as “murder,” or “killing” were not used. Instead, they used to employ the term “Couper: to cut”. They used to use the term “cut,” just like they say cut the trees, cut the leaves, or cut the branches.

(KS):

Thank you very much. I think that Director Rithy has gone beyond the question with his reply, one which leaves a lasting impression. There was however, another question such as “The guards didn’t look like they feel a sense of remorse or responsibility. Why is that?” I think the answer to this question can be found in the reply he just gave.

(RP):

I think that is an important issue which may also have something to do with our world today. Because it could also be related to such issues as for instance, when a similar event took place today, will it be possible for those caught up in fundamentalism to come back to human society and restore his or her humanity?

It is unfortunate, but crimes are something very human and I think they belong to human beings. It is sad, but don’t you think the act of committing sins to be something all too human? As sins are too human, if you say you are regretting, will that ever make you more human? That is a very complicated issue.

Now, another thing to be argued could be the level of their involvements in the crime. For this question, I don’t think there is a simple answer now, which can be applied to everything. Let’s take the example of Duch, the head of S21. Was he more responsible than those who actually engaged in the executions or did those who actually and technically kill people have a heavier responsibility? I think it is also difficult to measure such levels of responsibility.

Is it possible for those who had once been dehumanized and turned into slaughterers return to the fold of humanity or civilization? I think this question can be raised in relation to the extremist organization of Islamic State (IS) today.

Members of IS are chopping off the heads of the people brought to them from outside. It should be an issue of grave importance, whether these people can ever be reintegrated into the society. I am doubtful that they would be able to come back to human society or even civilization though it is very unfortunate for all the people.

Regarding the case of S21, those who were engaged in the crime there were aged between 16 and 20. And now, suppose they were asked to commit genocide again after 30 or 35 years, some of them might be able to do that again. However, other people cannot do the same thing any more. And all of them have sadness in their eyes. It cannot merely be explained through words. Words of remorse would never come.

Due to the process of dehumanization, words of remorse for killing people did not exist in the whole mechanism of S21. If they could have felt regret, they wouldn’t have been able to kill as well. They made them incapable of feeling any sense of remorse.

30 years have passed and now killing people is an illegal act, but you must remember that the genocide they had been engaged in those days was a legal act. The state was ordering them to commit genocide. They were members of the police or the security forces. They were just doing what was authorized and ordered by the state. As a member of the security forces called Santebal, they were killing the enemies to secure the public safety of the state.

So after 30 years or 40 years can they feel a sense of guilt? I think that’s doubtful. It may also be related to such issues as where the border of individual responsibilities of the crime lies, how to divide up individual responsibilities, and if it is at all possible to do that. It is also the same thing with Eichmann in Jerusalem who reportedly was just following orders. My feeling is, some of the S21 slaughterers might have been able to reject, to refuse killing people. In fact, there were some people who did reject it and transferred to different places from S21.

However, it is now difficult to judge whether they were good or evil to have killed people without rejecting orders, or to justify those who are feeling now a sense of remorse as good or evil. Perhaps, they will never be able to say the word “regret,” nor ask for forgiveness. The same is true of all the soldiers of the Khmer Rouge.

In addition, I assume that Dr. Kobayashi knows this very well as he has studied the Khmer Rouge and has been working on Cambodia since the mid 90s, but technically speaking, those workers at S21 did not use the term “Nokobal,” which generally meant soldiers of security forces. Instead, they used to call them “Santebal.” The naming itself was already a part of the elimination/genocide process.

Elites at S21 had another name. That was the name “pure tool of the party.” In this way, during the genocide, ideology would have a great effect, while peculiar language would play a big role.

Similarly, when the Rwandan genocide took place, they also had peculiar wordings on “RTLM” to call for “killing people.” At the same time, the speed of genocide would probably be important as well.

Eliminations at Jewish concentration camps only took little more than a year, and in Cambodia, the period of the largest scale of genocide lasted a year and half. With the case of Rwanda, I think it continued for 5 or 7months. The fact that 1.8 million people were slain in such a short period of time indicates the enormous speed of the genocide. When humans who look just like us became so radicalized to a great extent, will it be possible to technically bring them back to what they used to be? I doubt that.

(KS):

Thank you very much. We have received more detailed questions about relationships between the cast and the director. However, since we are running out of time, we would like to leave the topic on “S21” for now, and move on to the next set of questions.

Many of the comments we received were opinions that as we watch the movie “S21,” we should think about the issue as our own. For instance, these comments included “What should we do to avoid repeating the same thing?” “What kind of action can we take, when we are out of our usual time of peace and involved in a war?” and so on. In regards to these comments, I would like to ask a question to the Director. He has mentioned humanity several times. The leaders in the time of Pol Pot, be it Pol Pot or Khieu Samphan, had all studied in France and had completed their education of the time, learning and acquiring knowledge. Those people like Pol Pot came back from amid different cultures and then, shall I name it a source of humanity, the things that they were trying to realize…you also mentioned a comparison between barbarism and civilization. In that civilization, what was the most important thing? We should regard this issue as our own problem to think about the tragedies of genocide. I would like to hear your comments on this, if you have any.

(RP):

You gave me a long question. In fact, we might have to think about the roots of the revolution. The reason why we carried out a revolution we should give us pause for thought. I also think by myself, why I’m making films. When carrying out a revolution, it is to establish justice. I make films in order to accuse the absence of justice…to accuse the injustice. All revolutions have such origins. They are intended to realize justice, to realize democracy, and freedom.

The issue is what comes after the revolution. When you wish happiness for others too much, it could lead you in a different, dangerous direction, irrespective of your intentions. Once revolutions are over, it always leads you in such a direction. However, I think, as a matter of present, revolutions should continue for the foreseeable future. Our time is the time to carry out revolutions. Now, things are not all rosy nor going well, so we might need revolutions. Moreover, we are now in the time of absent ideology and due to its lack, a danger has emerged in which an inhumane and extreme liberalism is left to wield its power. I assume the absence of ideology is another problem today.

I think that returning to the roots of revolution and keeping up with our struggles is important. However, when revolution is realized and when you assume a position to make decisions instead of other people, I think possessing a certain level of modesty is especially important. Letting others live and paying respect to their lives should be very important.

I myself also survived a difficult time, but I find a motivation for life in the possibility to become happy and in the existence of happiness itself. Shouldn’t we see our lives in a positive way? Life is worth living and existence in itself has worth. I want to believe that in this way, it is worth it to maintain struggles as much as possible to look for solutions. Shouldn’t we teach these things to our children in schools from an early age? I think we should teach them to be tolerant to others and to live with others from their earliest childhood. Currently, people are not moving toward a direction whereby they can live together. They tend to withdraw themselves in their own shells and spend more time alone in front of the TV or tablets. Shouldn’t we teach them to live again with other people? Of course, such things might be easy to say but indeed, difficult to put in practice. It just seems to me that the rhythm of our life today is rather drifting in a direction whereby co-existence is being demolished.

However, we should not despair. I think we should keep up our efforts of directing our steps towards a correct path through trial and error, taking one step forward and two steps back, three steps forward and two steps back. Thus, the essential thing is the process of proceeding in a correct direction. In this way the importance of struggle lies in the act of waging it.

(KS):

Thank you very much. Well, in terms of time, we are coming near the end, but the next topic is about films, in particular, documentary films. One of them is about a film of the same nature or shall I say similar theme, entitled the “Act of Killing,” which deals with an incident in Indonesia. The question is what do you think about the movie or other movies in recent years which deal with genocide?

(RP):

I know the work of Joshua Oppenheimer, the “Act of Killing” very well. I also heard that my “S21” was a trigger for him to film part of his work. I could make more comments if he was here, but I don’t feel it is nice to do so in his absence. Regarding some areas in which I could not go further, for instance, due to personal reasons, he seems to have gone a bit too far. At times, things will be simpler for those who did not really experience it, those who are not the survivors of the genocide. I myself as a witness of the genocide and a party concerned, who survived that time, have something in some areas that I cannot dare to visualize. However, I think it is very good that different perspectives can be presented on the same topic of genocide. If I was to discuss the movie “Act of Killing”, it should be the proper way to screen the film first, and then I could make some comments such as “I like this point” or “I cannot really agree here.”

In order to explain how I practice documentary works, let’s take up a scene from “S21” again. In fact, when you make a documentary film with the theme of genocide, first of all, it is extremely important to be patient. You must possess a psychological measure for yourself. Moral is not really my favorite word, but you must have defined a moral regulation for yourself. I don’t like the term moral, so maybe I should put it in better terms: you must have an ethical regulation. When you are under strong shock caused by something ominous associated with death or violence, blood, and death itself, filmed images can possibly transform into something voyeuristic and vulgar. The very act of looking through a camera finder itself has a tendency to fall into voyeurism. Therefore, you must be very careful when you record a documentary film.

In some sequences of this movie, I stopped recording at some points. Because I knew if I went on, I would edit the film and use it to make a mistake. I stopped my camera in some scenes, thinking like this.

I still don’t know whether it was my natural reflex, or my instinct, or the dead around me that helped me make a better choice. In that sequence, a former guard of S21 was in the cell to reproduce the movements he used to do as in the past. A little longer shooting would have turned it into something disgusting for me. During the shooting, I made it a rule for myself not to enter the cell with my camera and not to follow the guard with a camera in my hand. Luckily, my camera did not enter the cell with the guards. Though, considering the sequence and the mechanics of the shot, it was quite natural for the camera to follow the guard and enter into the cell. However, I did not enter inside and stayed outside of the entrance of the cell on the opposite side. With three more steps forward, or even another step forward, my camera was to stand on the slaughterer’s side. That means I might have walked there trampling over the dead, the prisoners, who had probably been lying in the cell. I did not go beyond the barrier. That one step is a big difference. I don’t know what had stopped me, whether it was some instinct or something in myself. But when I look through the lens of my handheld camera, there are certain things that I feel I cannot record.

Documentary is an act of resistance. We shouldn’t record everything and we should stand against recording everything. Only by doing so, we can be fair to what is taking place in front of our eyes, in front of our cameras. Don’t give in to temptations produced by something sensational. Otherwise, it will be something voyeuristic.

Though I cannot teach this kind of thing to other people well, I sometimes give advice to young filmmakers about the documentary. My advice for them is “read a lot.” They might watch various movies, but watching a lot of movies won’t necessarily make them a good film maker. Rather, I would recommend them to read many poems or works by philosophers and writers.

This is because reading many books and increasing literacy will enable them to respect the dead and vanished people. I said vanished, but they have not completely disappeared. Their memories are still there and they exist there. It is important to respect the memories.

I often say such things. Thus, in that scene of the film, if I had followed him to the slaughterer’s side, I think it would have been a big mistake.

(KS):

Thank you very much. You have shared a lot with us today to think over but we are now behind our schedule by about 10 minutes, thus we must conclude our Q&A session. Please give a round of applause for the Director once again.

Documentaries line-up 2015

越境する東南アジア - Human Flows -

2人のマイケル / Michael's

監督:Kunnawut Boonreak

タイ北部にあるミャンマーとの国境の町メーソットとウンピアム難民キャンプを舞台に、マイケル・ライトと、マイケル・モハメッド、2人のマイケルに焦点を当てる。同じロヒンギャ※でありながらも、経済的な状況も育ってきた環境も異なる2人は、それぞれ生活に苦労しながらも、タイとミャンマーどちらにも属さないロヒンギャとしての自らのアイデンティティを保とうと奮闘する。

撮影地:タイ

line-up 2015祖父に捧ぐ / Dedicated to Grandpa Dieu

監督:Hien Anh Nguyen

ハノイ市内の騒がしい路地の小さな一角、質素な家で素朴な生活を営む祖父デューの日常生活を描く。デューは1960年代半ばに国連難民高等弁務官事務所でフリーランスの通訳者として働いていた野心家であり、懸命に好きな本を翻訳してきたが、その本を出版しようと試みたことは一度もなかった。(23min)

撮影地:ベトナム

line-up 2015儚さ / Fragile

監督:Bebbra Mailin

マレーシアのサバ州に住むインドネシア人家族の生活を、厳しい生活の中でも、歌手になるという夢を持ち続ける12歳の少女ニルワナの視点から描く。

撮影地:マレーシア

line-up 2015私の足 / My Leg

監督:Khon Soe Moe Aung

ミャンマーのカヤー州では、60年以上にわたり異なる民族の武装勢力が独立を求めてミャンマー軍と戦ってきた。敵味方の区別なく、年間約100足の義足を退役軍人たちに提供している退役軍人による義足店に焦点を当てる。(16min)

撮影地:ミャンマー

line-up 2015我が政治人生 / A Political Life

監督:Soe Arkar Htun

ユー・ティン・ソーは、若かりし頃にアウンサンスーチーのボディガードとして自らの青春を捧げ、政治活動に勤しんできた。長い間苦労をかけた妻と家族のために、政治活動から身を引くことを決断するが、それでも地元の人からの相談事は断れずに、法律相談にのってしまうのであった。(20min)

- 撮影地:ミャンマー

line-up 2015Documentaries line-up 2014 -People and Nature in Southeast Asia-

Documentaries line-up 2013 -Plural Co-existence in Southeast Asia-

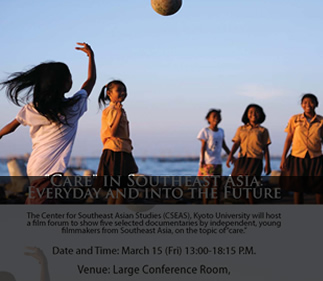

Documentaries line-up 2012 -“Care”in Southeast Asia: Every Day and into the Future-

監督紹介/ Directors

Kunnawut Boonreak

Born in Thai in 1990. Kunnawut Boonreak studied Journalism in Burapha University. Currently he is in master degree in Social Sciences and Social Development in Chiang Mai University. His first documentary “Laemchabang, the Wave of Sorrow” was nominated for Duke’s Award at the 16th Thai Short Film & Video Festival, Thailand in 2011. “Michael’s” received 2nd prize Duke’s Award at The 19th Thai Short Film Festival and also included in the official selection in 2nd Agitprop International Film Festival on People’s Struggle, Philippine in 2015.

Hien Anh Nguyen

Born in Hanoi, Vietnam in 1995. Hien Anh Nguyen was graduated from Viet Duc high school in 2013. Currently she is studying criminal law at Hanoi Law University. “Dedicated to Granpa Dieu” won two awards at the Bup Sen Vang 2015 Short Film Festival in Hanoi.

Bebbra Mailin

Born in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah. Bebbra Mailin was graduated from Master Degree in Film Studies at University of Sains Malaysia. She has been involved in a number of well received short film productions in Sabah and Peninsular Malaysia. In 2011, her first experimental short film “Eye Love” won the Kota Kinabalu International Film Festival for Best Film. In 2012, she participated in Borneo Eco Film Festival for her second short film “Langad di Odu (My Grandma’s Longing)” and won the Best Film category. Currently, she lectures at Faculty of Film, Theatre and Animation in film department.

Khon Soe Moe Aung

Khon Soe Moe Aung lives in Kayah and works with youth and environmental groups.

Soe Akhar Tun

Soe Akhar Tun is a computer Science graduate. He is a member of Yangon Film School. His film “A Political Life” is his first documentary.

Requirements

Requirements to submit documentaries are as follows:

1. Applicants must be Citizens of Southeast Asia or Japan.

2. Documentaries should be no longer than 30 minutes.

3. Submissions should be productions made after January 2014.

4. Directors should make sure they have permission from any subjects that appear in the movies.

5. Documentaries should include English subtitles.

6. Translation and subtitling is also the responsibility of director(s)*

*Selected documentaries will be screened in their original languages with both Japanese and English subtitles. However, documentaries that are in English will only have Japanese subtitles added and vice versa.

Invitation to Japan

An international selection committee will select five successful documentaries, and invite the director(s) of each movie to Kyoto and Tokyo, Japan for an international screening. The Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS), Kyoto University will cover travel and accommodation fees.

Applications

1. Please upload online a copy of the production with subtitles in English/Japanese. Applicants should also submit a synopsis (no longer than 700 words) that describes the documentary and a C.V by attachment. Apply via http://www-archive.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/sea-sh/vdp2015/

Conditions for uploading films

(a) Films must be submitted in a format supported by YouTube.

(b) Films must be produced in accordance with their purposes and not defame the Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS).

(c) Films that are uploaded should not infringe upon the rights or interests of personal or organizational copyright holders.

- Any background music (BGM) included in films must be copyright free or have the prior permission of copyright holders to use in said films.

- For any images from cartoons, literature, television or films, directors must make sure that copyright has been transferred from those that own them.

2. The Center will announce the finalist results on the 12 January 2016.

3. Selected documentaries will be uploaded to a website for public viewing.

Other

1. Documentaries will be archived (with the permission of the director(s)) on-line on the Center’s website.

2. Copyright remains with the director of the documentary at all times.

3. The Center will not fund any requests for production funds, the purchase of recording equipment or editing software.

For any inquiries please contact vdp[@]cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp