Myanmar is the third most landmine-contaminated country in the world after Afghanistan and Colombia. According to Displacement Solutions (DS), an organization that employs a rights-based approach to assist forced migrants around the world, perhaps as much as five million acres nationwide are contaminated, the most heavily affected areas being the country’s border regions due to nearly 70 years of low-intensity armed conflicts (Displacement Solutions 2014). The rugged terrain, tight travel restrictions, the almost complete absence of systematic data on the location of known hazardous areas, as well as the frequency of accidents, mean that the actual scale of the problem is not accurately known, however. These uncertainties present varying degrees of risk to everyone living in landmine-contaminated areas, but especially for the country’s estimated 370,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) and 480,000 refugees (UNHCR 2015). There is widespread recognition there is a need to clear travel corridors and to establish landmine-free areas for forced migrants who wish to rebuild their lives in former conflict-affected areas. But a range of actors currently oppose humanitarian mine action (HMA), which entails risk education, clearance victim assistance, advocacy, and stockpile destruction, on the grounds doing so now presents a threat to the on-going peace process.

Fig.1 Foot prosthetics for landmine victims, Mae Sot Thailand

Mine Rise Education (MRE) consists of educational activities designed to raise awareness and promote behavioral change to reduce the risks landmines pose. To my surprise, nearly all of the NGO representatives that I interviewed in Thailand and Myanmar stressed MRE remains a “very sensitive topic,” so much so that the political space for implementing it is extremely limited at present. The question is why given that rural populations in landminecontaminated areas obviously face direct risks to their physical wellbeing. I found that other actors, such as government entities, state and non-state armed groups (NSAGs), development agencies, NGOs, and business enterprises bear other kinds of risks. When the interests of these actors are taken into account, MRE ceases to be a universally desired good because it contributes to new harms even as it reduces others.

DS carried out a stakeholder consultation process in mid-2013, during which they spoke with nearly one hundred individuals representing landmine-affected communities, civil society organizations, and community- based groups, as well as local and international NGOs involved in HMA and some NSAGs. (The country’s armed forces did not participate.) Based on its findings, DS outlined the 14-step sequence for operationalizing land-sensitive HMA in accordance with its eight core principles. The “Do No Harm” approach, one of the co-authors of the report told me, wrongly assumes that the risks associated with moving forward with landmine clearance can be managed, even without having the procedural and practical mechanisms in place to adjudicate conflicting property claims or provide legal recourse to people who have had their land seized.

One Humanitarian Disarmament Program Manager, for example, noted that the report’s emphasis on housing, land, and property rights, although critically important for the success of HMA, was premature. Some NSAGs, such as the Karen National Union (KNU), recognize customary or traditional land rights in areas they administer. However, the government currently does not, he explained. Consequently, people in (former) conflict-affected areas do not enjoy adequate protection under the law, and organizations involved in HMA do not have the expertise or authority to assist them. More pressing, he explained, was the Myanmar Mine Action Center’s apparent reluctance to authorize and to coordinate MRE, much less mapping and signposting hazardous areas. “There’s been dialogue with the Myanmar Peace Center and there was complete agreement on everything, right down to the number of cleaning ladies that needed to be hired. But again, it didn’t happen. The money is just sitting there.” The Peace Center, he reported, provided some vague statements indicating that, “it was not yet appropriate to begin discussing operational plans,” but it took them a full year before they stated directly that it would “have to wait until the Tatmadaw and the NSAGs had buy-in post-ceasefire.”1) No one is officially allowed to do anything beyond MRE for this reason, he stated.

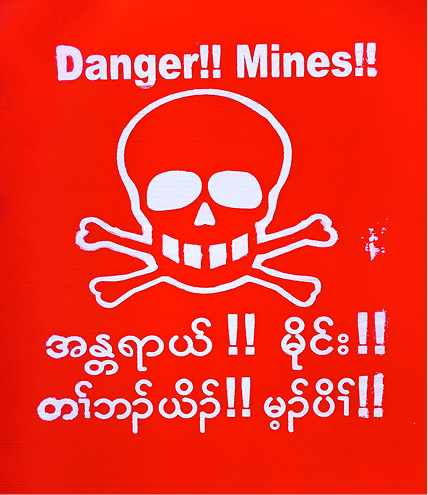

Fig.1 Landmine warning sign, Karen State

Many people share his frustration with view that MRE is “very sensitive.” A national MRE coordinating group consisting of government and non-government organizations exists, and it is reasonably effective in terms of data collection regarding landmine accidents, as well as the number of workshops held and training materials distributed. But there is significant disagreement on the content, which is emblematic of the broader problem: the people most in need of MRE are not able to easily obtain it. For example, the Chief Minister for Karen State announced that all ongoing MRE activities had to stop immediately on the grounds that “it was not yet the right time,” but his office did not provide any further details, one foreign MRE trainer told me. It later turned out that a photograph in the MRE materials, which UNICEF and DanChurchAid Mine Action had prepared using a photograph from Cambodia, was the source of the problem. The photograph depicted a soldier, wearing a nondescript uniform, laying a landmine. In the Minister’s opinion, the image “might harm the peoples’ respect for the [Myanmar] government.”2)

MRE also remains a problem on a practical level. A MRE trainer for the Committee of Internally Displaced Karen People (CIDKP), the humanitarian wing of the KNU, told me that the existing curriculum, based on the one used in Cambodia, encourages rather than discourages risky behavior. “I teach many things that are not in it, and I do not teach everything that is.” He explained, “booby traps are common in Cambodia, but in Burma/Myanmar they are not. One time I taught villagers about them [after they expressed desire to learn more about the pictures on the flipcharts]. They thought they were great. They wanted to make some for defensive purposes!” Mutual suspicion is a significant problem as well. “Marking hazardous areas is a non-starter at the national level,” a technical expert with the Mine Advisory Group said. In fact, MMAC “is downright hostile to the idea,” the expert continued. So, too, are NSAGs, which assert that doing so makes them vulnerable tactically. (NSAGs currently regard systematic mine removal and destruction, like disarmament more generally, as “surrender.”) Consequently, local Karen organizations that for safety reasons want to identify suspected hazardous areas and signpost known ones in non-strategic areas regularly face accusations that are government collaborators, even though many of them have provided invaluable humanitarian assistance to their conflict-affected communities for decades.3)

Many domestic NGOs, civil society organizations, and community-based groups are also concerned about the tremendous increase in foreign assistance Fig. 1 Foot prosthetics for landmine victims, Mae Sot Thailand Center for Southeast Asian Studies Kyoto University 009 to Myanmar. They assert the assistance supports the proliferation of government networks in areas where they previously had little or none and undermines already existing local ones that provide social services, especially health and education, to their respective conflict-affected communities. The Director of the Burma Relief Center, a cross-border humanitarian organization, describes this increase as an “aid offensive.” “The current situation is now critical,” she stated. “Aid is drying up here, and the funds, which are going inside, are supporting government structures in one way or another. In the process, they are undermining the structures that community-based organizations built up over the years, and that is a serious problem. The ethnic movement is in greater danger.”4) A Karen research analyst for the Salween Policy Institute calls it the “development offensive.” He cited the blueprint for development in Southeastern Myanmar the Japanese International Cooperation Agency and the Ministry of Border Affairs released relatively recently.5) The blueprint emphasizes the construction of economic corridors, agroindustrial clusters, as well as free trade zones and industrial estates with the assumption that conflictaffected populations will want to work in them. (A sizeable percentage of them will have to pass through landmine-contaminated regions to do so, he pointed out.) Not everyone shares this assumption, however. More than 30 civil society organizations that operate in the target region quickly issued a detailed critique of the neoliberal model for border economic development, which they claim was prepared without input from people living in it and without public consultation afterwards. This is why economic development poses a threat to its own realization. Economic development, which requires demining in conflict-affected areas, will be impossible without HMA. But HMA, even if carried out in accordance with international best practices, may destroy what decades of military offensives did not: the possibility for these communities to make informed decisions about what form their own futures should take in post-conflict Myanmar.

The urgent need for HMA in Myanmar is the product of an enduring crisis. Living conditions in most conflict-affected areas are such that organizations are urging donors, the government, and NSAGs to take immediate action to address the humanitarian emergency that exists in the country’s border regions rather than wait for a nationwide ceasefire agreement, much less one regarding post-conflict political arrangements. Yet, these key decision-makers resist labeling this crisis a “crisis” in the name of furthering the peace process.6) Armed parties regard any effort to change the status quo, including MRE, as having the potential to undermine the “new” normal, which is neither resumed war nor a genuine peace, but something in-between. Consequently, landmines possess potentiality, one that enables them, even as lie underground, to exert form of agency—albeit one without intent or directionality, which is what makes their removal currently so explosive in contemporary Myanmar.

References

Displacement Solutions. 2014. Land Rights and Mine Action in Myanmar. Geneva: Displacement Solutions.

UNHCR. 2015. UNHCR Country Operations Profile.

Notes

1) Interview, Aksel Steen-Nilsen, Norwegian People’s Aid

Humanitarian Disarmament Program Manager

2) Interview, Anonymous, Committee of Internally Displaced

Karen People staff member

3) Interview, Eh Thwa, Mae Tao Clinic Mae Sot Prosthetics

Clinic Director.

4) Interview, Pippa Curwen, Burma Relief Center Director.

5) Interview, Saw Greh Moo, Salween Policy Institute analyst.

6) Interview, Nilar Myaing, The Border Consortium-Yangon

Director.