The democratized atmosphere of the post-Suharto era (after 1998) has provided wider room for Indonesian women to expand their political role in a number of ways, including participation in direct elections and securing leadership positions. Since the early 1990s, Muslim women activists in Indonesia have begun to embrace and spread ideas of Islamic feminism through publications and discussions. Subsequently, since the early 2000s, non-state actors from academia and women activists began to promote affirmative action regulations to increase the representation of women in parliament. Increasing discussions on gender equality in Indonesian Islam and civic consolidation to foster government’s policy of pro-affirmative action, resulted in voluntarily affirmative action being adopted in the 2004 General Election. This was followed by firmer affirmative action rule combined with the zipper mechanism (male and female candidates who would appear alternately on party lists) which required at least one woman among the top three candidates in the 2009 General Election, and then in the 2014 General Election. In the forthcoming 2019 General Election, Law No. 7/2017 article 173, section 2 (e) set the requirement that only a political party that is able to fulfil the affirmative action rule, where women make up 30 per cent of the members of party’s managing officers on the central board to compete in the General Election. Although the representation of women in the Indonesian parliament is still below 30 percent, the vibrant discourses surrounding it have provided comfortable spaces for greater political participation and the leadership of women, including in Indonesian Islam.

Machrusah (2005) studied Muslimat Nahdlatul Ulama (Muslimat NU), the women’s wing of NU, a traditionalist Muslim organization founded in 1926, to observe how it negotiated with its male dominated parent organization NU for greater gender equality. Machrusah concluded that the reinterpretation of religious texts is only one part of a discussion in talking about better gender relations within traditional Muslim societies as it also depends on external political forces. “'Aisyiyah,” the women’s wing of Muhammadiyah (the Islamic modernism movement in Indonesia founded in 1912), also proposed women’s leadership. Taking an interest in these changes in Indonesian society, in 2006, I begin research on women’s leadership in Muhammadiyah. My work revealed that 'Aisyiyah have demanded for women to be included in the Muhammadiyah Central Board since the 40th “'Aisyiyah Muktamar” in Surabaya 1978 (Dewi 2008, 166). Muhammadiyah’s formal religious perspectives is in favor of women’s leadership; in contrast to the majority of Muhammadiyah followers at wilayah (provincial) and daerah (district) level who oppose women’s leadership as they are likely dominated by textual approaches in interpreting divine messages on women’s leadership. This was the case with the 45th Muhammadiyah Muktamar held in July 2005, where no women were elected to the Central Board of Muhammadiyah (Dewi 2007; 2008). I concluded that 'Aisyiyah’s demands for women’s leadership in Muhammadiyah should consider the changing religious perspectives of Muhammadiyah followers in favor of women’s leadership, their ability to engage with obstacles from the gendered perspective of Muhammadiyah’s development, and from within the context of Javanese culture (Dewi 2007; 2008).

Contemporary discourses and pressure for women’s leadership in Indonesian Islam, namely NU and Muhammadiyah, coincides with the ongoing development of local politics. Direct local elections to elect heads of local government under the Law No. 32/2004, was initially implemented in 2005. I have argued that structural opportunities for women to be recruited into politics have increased under the new conditions for direct local elections (Dewi 2015, 8). Today, female politicians can move freely among voters without running into barriers set up by oligarchies and male-dominated political parties. This is because direct elections have lessened, if not removed, the institutional barriers of oligarchic, male-dominated political parties, including inside the regional People’s Representative Council (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah, DPRD), which had been the mechanism through which local government heads were elected. It is now the voters who decide who wins, and not male dominated political elites inside DPRD, who formerly elected local leaders. The number of female leaders elected via direct local election as governor/ mayor/district heads, have increased significantly in which most of them are Muslims in Java, since the introduction of direct local elections in 2005. This new development is influenced by the increasing engagement of Indonesian Muslim women who hold Islamic principles. To put it another way, contemporary Indonesian Islam in the post-Suharto era shows a waning of political Islam, but a deepening of “social Islamization” (Ota et al. 2010, 3–5). Considering this context, I suggest that the increasing number of female Muslim leaders elected through direct elections indicates that important changes and developments have taken place in Indonesia in relation to Islam, gender and politics.

In 2008, I started new research on Muslim women political leaders focusing on three Muslim women political leaders who won direct local elections in Java. The majority of elected Muslim political leaders are in Java and Javanese. Observing Indonesia’s local politics through the prism of gender, my ongoing research has revealed many positive, yet often neglected factors, namely the role of Islam, gender, and networks behind the success of Muslim women political leaders in direct local elections. Concurrently, I have been developing new perspectives on the agency of Muslim women in utilizing their individual capital (education, social background, gender) (Dewi 2012; 2015). In particular, I have highlighted two mainstream Indonesian Islam organizations, namely Muhammadiyah and NU that have similar perspectives and attitudes in supporting women’s leadership in local politics, where the three female Javanese Muslim political leaders exercise power (Dewi 2015, 63). Thus, Indonesian Islam provides a strong religious foundation for Muslim women political leaders to expand their leadership in politics and shape the growth of democratization in post-Suharto Indonesia.

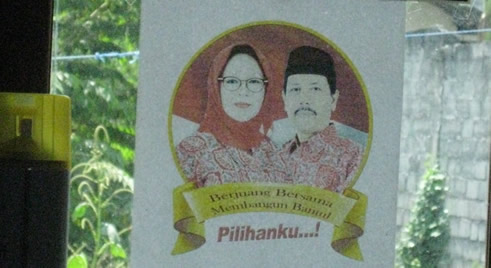

Photo: Kurniawati Hastuti Dewi

Finishing my study, I was further driven by curiosity to uncover another two factors, piety and sexuality, which I did not deeply explore in my earlier research. In doing so, in 2016, I observed another four Muslim women political leaders’ experiences and narratives, who resided in Yogyakarta Province and other surrounding provinces. Research showed that private lives and intimate relations, which are greatly shaped by Islamic norms, such as wearing the veil and husband- wife relationships, are deliberately brought into the public sphere to seek political sympathy. Their actions tell us that it is not only the agency of these four women that matter; the veil itself is a means of agency. The veil, rather than signifying oppression as often perceived by western feminist understanding, becomes a progressive socio-political tool because it gives them comfort in certain spaces to maneuverer and participate in the public sphere which is highly patriarchal, given the increasing engagement of Indonesian people with Islamic principles and norms in the third wave of Islamization in Indonesia (Dewi 2017a, 344, 354). Wearing a veil, in this case, signifies freedom for Indonesian Muslim women to take active part in electoral politics. I also discovered that the piety and good sexuality of Muslim women political leaders may be only be a very superficial part of their attitude, being able to get wider approval and power. This finding confirms an earlier analysis of three Javanese Muslim women political leaders where ideas and norms of Islamic piety in public sphere were played upon or used in political campaigns, beyond a personal act of worshipping God(Dewi 2015, 182). This public piety is intermingled with sexuality. There are generally widespread norms of Indonesian society that perceive heterosexuality as the acceptable norm: the four female Javanese Muslim politicians are expected to behave with their spouses (husbands) as good wives and mothers, and this clearly played out in their political campaigns (Dewi 2017a, 354). Although we should be aware of the “conservative turn” (van Bruinessen 2013, 3) phenomenon of Indonesian Islam, research suggests that in local politics, gender is not a significant element of contestation that can be used as a primary point to attack or hinder Muslim women candidates.

Fig.2 Kurniawati Hastuti Dewi interviewing SW district head of BT (2010–2015), 31 July 2016.

In-depth research on women’s leadership in Indonesia (2006–2017) suggests the importance of updating previous notions regarding female leadership in Asia that rely heavily on the “familial ties” factor and notion of “moral capital” (Dewi 2017a, 343). I suggest that without neglecting the importance of personal capabilities, we should consider and pay attention to ideas and practices of Islamic piety and sexuality in the public sphere to analyze the rise of Muslim women’s political leadership in Asian popular democracy; in a milieu of Islamization and globalization in the twenty-first century where discourses of piety and sexuality are becoming increasingly dynamic.

Through years of research, I realize that a feminist research methodology, one that focuses on women’s personal experiences in a specific context to gain knowledge based on their real-life experiences (Harding 1987, 30), has enabled me to capture not only their experiences, but much more. By positioning women as a source of knowledge, we can observe the correlation between Islam, gender, networks, piety, and sexuality in the public sphere of contemporary Indonesia. The agency of Muslim women political leaders is pivotal. Their thoughts and experiences have produced new narratives of Indonesian Muslim women’s roles and positions, namely those who actively create opportunities in politics with confidence to embrace and expand new meanings of Islamic piety into the public sphere. This is shaping the growth and direction of Indonesian democratization which was previously mainly dominated by men. Nevertheless, academic efforts to promote women’s leadership or political research with gender or women’s perspectives faces contemporary challenges. Both the public and academia have higher expectations toward female political leaders’ commitment and achievement toward gender responsive policy. Careful analysis is needed in viewing this matter. Research has made clear that most female political leaders show low commitment or passive roles in promoting gender responsive policy, which has been influenced by a number of factors such as their personal experiences, their engagement with women’s groups during their quest for power, and their leadership characteristics (Dewi 2015, 174, 183). Additionally, so far, the majority of female political leaders come from strong families ties and political dynasties which prevent them from performing progressively in a different fashion from male oligarchs (Dewi 2017b). Furthermore, there are an increasing number of female political leaders who have been jailed due to corruption cases (such as in Banyuwangi, Banten, Klaten, Tegal, Kutai Kertanegara). Although many male political leaders have also been jailed due to corruption cases, the public have paid special attention to the performance of female political leaders. This is due to their rise and it is still regarded as a new phenomenon which has disrupted a predominantly male dominated political landscape. This development indicates a disparity between academic efforts to promote women’s leadership, as well as research on politics with a focus on gender and women on the actual situation of women’s leaders in Indonesia.

This situation, if not paid enough attention, will result in a backlash against the efforts to promote women’s leadership in Indonesian politics. Finally, one other challenge is to encourage more female political leaders from lower class groups to participate. To date, female political leaders in local politics have predominantly come from the middle-class. While lower class women usually do not have enough resources to compete in direct local election, middle class women have acquired better individual capital (in the form of education, finance, and skills), as well as social capital (networks). These are all requirements to compete in direct local elections. Certainly, there is still much to do to narrow the divide between normative expectations and the actual situation of women’s leadership in Indonesia. Systematic and continuous effort needed to achieve substantive narrative women’s leadership, beyond the symbolic narrative of women’s leadership in Indonesia.

References

- Dewi, Kurniawati Hastuti. 2007. Women’s Leadership in Muhammadiyah: ‘'Aisyiyah’s Struggle for Equal Power Relations. Master's thesis, Australian National University.

- ––––––––. 2008. Perspectives Versus Practices: Women’s Leadership in Muhammadiyah. SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 23(2): 161–185.

- ––––––––. 2012. The Emergence of Female Politicians in Local Politics in Post-Suharto Indonesia. PhD thesis, Kyoto University.

- ––––––––. 2015. Indonesian Women and Local Politics: Islam, Gender and Networks in Post-Suharto Indonesia. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press; Kyoto: Kyoto University Press.

- ––––––––. 2017a. Piety and Sexuality in a Public Sphere: Experiences of Javanese Muslim Women’s Political Leadership. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 23(3): 340–362.

- ––––––––, ed. 2017b. Perempuan Kepala Daerah Dalam Jejaring Oligarki (Female Political Leaders in the Oligarchy Networks) Lokal. Jakarta: LIPI Press.

- Harding, S. 1987. The Method Question. Hypatia 2(3): 19–35. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3810120.

- Machrusah, Safira. 2005. Muslimat and Nahdlatul Ulama: Negotiating Gender Relations within Traditional Muslim Organisation in Indonesia. Master's thesis, Australian National University.

- Ota, Atsushi; Okamoto, Masaaki; and Ahmad Suaedy, eds. 2010. Islam in Contention: Rethinking Islam and State in Indonesia. Jakarta: The Wahid Institute, CSEAS, and CAPAS.

- van Bruinessen, M., ed. 2013. Contemporary Developments in Indonesian Islam: Explaining the “Conservative Turn.” Singapore: ISEAS.