Introduction

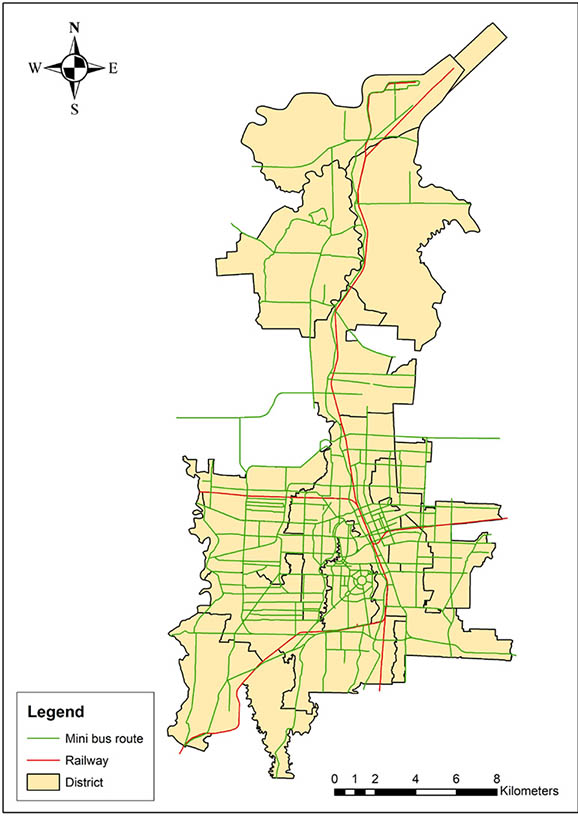

PFig. 1 Map of Medan city with its public transport network (Source: Bappeda Medan, 2018)

Medan (Fig. 1) is the third largest city in Indonesia after Jakarta, and Surabaya. It is the capital city of the North Sumatra province, with a population of 2.5 million. Compared to other big cities in Indonesia, Medan has the second highest vehicle ownership per person which consists mainly of motorcycles (73%) (Joewondo et al. 2007). Out of all vehicles in Medan, only one percent is public transport vehicles (Project Pipeline 2018). Due to this it is no wonder that traffic congestion is no longer restricted to peak hours but at all times in the city, along with air pollution and traffic noise (Surbakti et al. 2011). This article describes my experience of Medan transportation during a recent field trip.

Medan is only one hour flight from Kuala Lumpur, which means it is nearer to Malaysia than to another city, like Jakarta in Indonesia which takes about two hours. At the airport, travelers can be seen waiting to catch the shared taxi to Parapat, where the famous Lake Toba (the largest supervolcanic lake in the world) lies. Connecting Kualanamu airport to Medan's city center is the Airport Raillink Service, which is proudly the first airport train service in Indonesia. The station building looked very new, and the service comes once every hour. Tickets were given in the form of barcodes, which could only be bought from vending machines using credit or debit cards at IDR 100,000 per person. On the train that took 30 to 45 minutes, local housings and settlements could be seen along the journey.

Arriving at the rail station in the city, I immediately snapped out my mobile phone and tapped on the local popular ride hailing application: Grab. In Indonesia, ride hailing transport services are an extremely thriving business. The three companies that offer services in Indonesia are Grab, Gojek and Uber (Oxford Business Group 2018). Both Grab and Uber are also available in Malaysia; while Gojek is an Indonesian local business. The competition between Grab and Gojek is especially intense, with all kinds of services being provided. People can choose to travel using the cheaper and faster GrabBike/Go-Ride or the more comfortable GrabCar/GoCar. Other extended services include delivery of food, groceries, courier, and even pharmaceuticals. Such services offer great conveniences to locals and visitors like me. The entire journey from pick up to reaching destination is tracked through GPS real time in the online application, which ensures both efficiency as well as passenger safety to some extent. At the end of the journey, fees can be paid using the cashless online payment system (OVO) in Indonesia, saving the trouble for drivers to return small change. This business has offered mass job opportunities for locals, and alternatives to travel in an affordable way without owning one’s own transport.

Despite all these conveniences, I wonder how this business changes the local transport system in Medan, and its long-term impacts. In particularly, people’s travel behavior in terms of number of trips, kilometers travelled and travel mode could significantly influence the amount of urban emissions for both greenhouse gases and air pollutants. In other cities with sufficient public transit infrastructures, ride hailing service has been seen as the savior for the first and last mile connectivity, which could encourage the ridership of public transits (Bliss 2018). However, in the case of Medan city where transit infrastructures are still developing slowly, how do ride hailing services contribute to urban sustainability aside from its socio-economic benefits? Besides, the operation of the service itself could contribute to the extra exhaust fumes. What do the ride hailing drivers do on their vehicles while waiting for a customer’s call? Even an idle vehicle could emit fumes from running engines. And in addition, more trips may have been produced from the deadhead journeys from picking up passengers and returning from destinations (Schaller 2018). The local transport agency may need to consider where to place ride hailing services in the urban sustainability framework when more public transit options are built in the city (Sperling et al. 2018).

Fig.2 Chaiwat Sahta-Anand giving a Keynote Speech

Out on the road, I was immediately greeted by the hectic traffic of the city center. Incessant honking filled the air, which was a way of warning to ‘be careful’ from concerned drivers. However, local people along the road seemed oblivious to it. The mixed mode traffic consisted of automobiles, motorbikes (many in the green uniforms of Gojek or Grab), Angkot (local public transport), motor rickshaws (becak), and most noticeably, nonchalant pedestrians trying to cross the road (Fig. 2). Most of the roads were without lane lines, as drivers crisscrossed against each other to make their way forward in congested traffic. According to Joewondo et al. (2007), there was only 24,533m2 road markings in the city with 3,079km of roads. I was both amazed and worried for the owner of a motor rickshaw which was going in the opposite direction of the traffic. However, it seemed to be nothing of concern as drivers skillfully avoided it. For the pedestrians, crossing the roads even those with traffic lights was dangerous as some motorbikes just ignored the signals. At places without traffic lights, people were forced to cross the roads just like that. I tried to cross roads a few times which took forever as I waited for the time when there were fewer cars, which never came. It was actually safer to cross during heavy traffic than less traffic as vehicles tend to speed along the way. My acquaintance in Medan said that you need skills and bravery to cross the roads in Medan. I never grasped the necessary skills, and had to muster great bravery standing in the middle of traffic trying to cross roads.

The destinations in the city centre itself were actually very near to each other in its dense arrangement (ITDP 2014). However, due to an unfavorable walking environment among the traffic noise, I believe people would not choose to walk. Traffic lights were scarce even in the city, and were mostly designated at locations for vehicle traffic (such as crossroads) and not pedestrians. At some point along the walking path, one would definitely need to cross the busy road to get to a destination. Furthermore, crime was a concern in Medan especially snatch robberies. I had been warned several times to be careful walking in the city. Other than the local train which I have yet to explore, another public transport in Medan was the Angkot, a van-like vehicle with opened doors for passengers. The Angkot picked up and dropped off passengers literally anywhere on the road along the way. There were different numbers and colors to the van, representing different companies. However, the fastest, and perhaps the most secure way to know which way the Angkot was going, was asking the driver directly himself as there were no official guide to the routes of the system. There had been numerous times that I saw Angkot drivers maneuvering recklessly on the busy roads. As for the motor rickshaws (I could hardly see any bicycle rickshaws), they were another kind of local transport unique to Medan. They could be seen everywhere in the city looking or waiting for customers beside the roads. Sometimes, they charged extravagantly for a short journey, especially if they caught a hint that you were not a local. Prices had to be negotiated with the rickshaw driver before the journey. Due to such inconvenience, it is no wonder that people were shifting from the traditional transport to ride hailing services as it is safer and more cost efficient with fixed rates (Smith 2018). If the local public transit sector still does not improve and develop fast enough, I believe the ride hailing service will continue to flourish rapidly and take over the role of public transport among the local people in no time.

Conclusion

The transport system in Medan city is still very much dependent on automobiles, both cars and motorbikes. The increase of both ride-hailing drivers and users casts doubts, on their roles in the long-term urban transport sustainability. Ultimately, it is about reducing the vehicle kilometers travelled rather than automobile ownership or passenger kilometers travelled in the aim of achieving sustainability. Hopefully the local planning agency will give more thought to incorporating an organized public transit system and walking infrastructures in the future planning of Medan city. This will create job opportunities as well as offering more travel options that can compete with the ride hailing service. Currently, a 21km Light Rail Transit project is being planned, which will be integrated with Bus Rapid Transport (BRT) to form a mass public transit system in Medan (Project Pipeline 2018). However, these public transport systems will be incomplete without well-connected pedestrian lanes especially at the destination end. At least, as a start, it would be nice to see some measures for safe pedestrian crossings at the city centre on my next visit.

References

- Bliss, L. Aug 3, 2018. Where Ride-Hailing and Transit Go Hand in Hand. CityLab. https://www.citylab.com

- Institute for Transportation and Development Policies (ITDP). Apr 29, 2014. A Look at Life and Transit in Medan, Indonesia. https://www.itdp.org

- Oxford Business Group. 2018. Popularity of Ride-hailing Apps Surges in Indonesia. https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com

- Project Pipeline. 2018. Medan City Urban Transport Project. https://pipeline.gihub.org

- Schaller, B. Jul 25, 2018. The New Automobility: Lyft, Uber and the Future of American Cities. http://www.schallerconsult. com

- Sperling, D., Brown, A., D’Agostino, M. Jul 5, 2018. Can Ride- Hailing Improve Public Transportation Instead of Undercutting It? https://www.scientificamerican.com

- Smith, M. Mar 25, 2018. Ride-hailing Apps Run Indonesian Tuk-tuks Off Road. https://phys.org

- University of California Davis. Aug 31, 2018. Ride-hailing Apps Like Uber are Reducing Public Transport Use in the US. But They Could Do the Opposite. https://www.citymetric.com