In 1993, large-scale rituals were held at Besakih temple in Bali. Realization of such spectacular rituals at the grand head temple of Hinduism in Indonesia seems to assure the establishment of the religion, even as a minority. In the background, however, there was a deepening conflict between the Bali-centrists, who regarded rituals and practices in Bali to be essential to Hinduism in Indonesia, and the faith-centrists, who adhered to Hinduism as a faith that has spread across the globe. At the turn of 21st century, the representative institution, supposed to protect Hinduism, failed to resolve the conflict, which has resulted in a schism.

Large Scale Rituals and Manuals

In 1993, a series of large-scale rituals were carried out in the central temple of Besakih in Bali, Indonesia. Since the centennial ceremony held in 1979 at the same temple had turned out to be lacking some parts, they were carried out in 1993. Despite being called centennial, the only proof available is the palmleaf manuscript reporting the existence of the rituals, hence, it is not certain if they had really been conducted a century ago. Furthermore, according to an essay written by a traveler from the Netherlands, the country that had colonized Indonesia, the temple had collapsed and not been functioning as a temple prior to an earthquake in 1917. Though the rituals held in 1993 were based on the dates on the calendar, they only existed in documents and not in the memory of the living people. In other words, they were brandnew rites that had not been embedded in their practice.

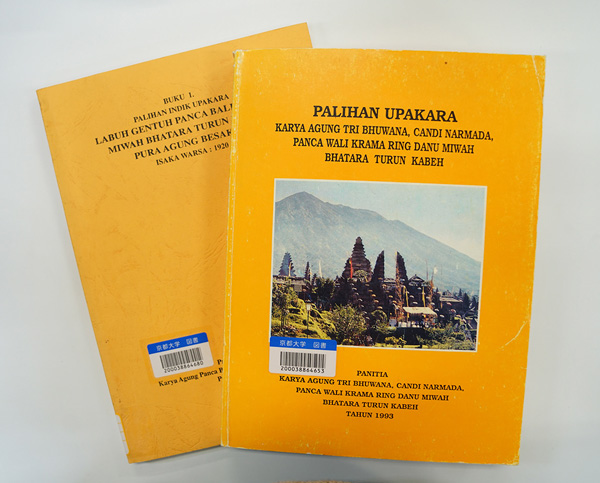

As such, how was it possible to perform such new grand rites? The only way to construct the rituals was to refer to names of the rites and offerings recorded in documents and to know them through analogies. The thick yellow book with the name of the rites inscribed on its cover is what it called a manual with descriptions of the formulated ritual proceedings. And the rituals were reduced to practices based upon this manual. The practices prescribe the procedures, yet this does not mean there was any precedent for them to be manualized. This manual was the source of the reconstructed grand rituals as they were, that no one had ever seen before.

Manuals

The rituals were grandiose, in the sense that they accompanied multiple rites held in each temple of Besakih, as a complex of multiple temples, and that the scale and the number of offerings involved in each rite could amount to a maximum. The offerings included performances of gamelan music and dance. Everything was written down in the manual in chronological order, such as how the priests conduct each rite, offerings and work groups for preparations.

The enormous preparatory works were shared among parties including groups which possessed temples, as well as different districts constituting the province of Bali. In each district, they followed instructions given by the designated priests to proceed with works. Such division of labor was enabled by the cooperative system between the representative institutions of Hinduism in Indonesia, known as Parisada Hindu Dharma (Parisada) and the provincial government of Bali that had begun to be formed prior to 1979, culminating in the 1990’s.

As Parisada’s priests specified the details of the rites, two committees, the central one established in Besakih and the local one in each district, gave instructions for the works. The highest position in the central committee was held by the provincial governor, while the second highest, were occupied by those inspectors including the Hindu Department head of the Ministry of Religious Affairs alongside the district governor. Though executed through the channels of the provincial administration, this was an indication that the Hindu rituals were for the whole nation. And what was handed out at the general meeting of the central committee was this manual. It was only delivered to the parties to the conference and was of course, not for sale. However, it was obtained by one of my research collaborators who had attended the meeting as a note-taker.

Accepting holy water with the temple

The Individual and the Symbolic Cosmos

What kind of funds helped to realize the grand rituals in 1993? The provincial government had provided reserves prior to the rituals, though they were untouched in the end. The grand rituals themselves were fully funded by donations from individuals and organizations.

For the implementation of the rituals, the provincial government had prepared booklets for the individuals that described the guidelines and significance of the rites, the way to receive consecrated water, as well as ritual procedures to be observed at individual homes and villages in tandem with those at Besakih temple. It also referred to appropriate manners as a good Hindu to participate in rituals. To be more specific, it obviously suggested that they are required to have a clean mind, speech and deeds in order to accomplish the sacred rites, and that they should take part in the rites, offering material or monetary contributions for the rituals willingly and according to their own capacities. Material contributions implicate rice, fruits as ingredients for the offerings as well as sweets and so on.

For individuals, clear prescriptions on how to receive consecrated water was very significant. What is fundamental to rituals in Bali is the priest who turns the water sacred through rites and those individuals who receive it. In the case of a large-scale ritual, they would specify the date, time and place for the delivery of consecrated water to be picked up by village representatives, who would then distribute it to each household. Thus, as the flows of materials and financial participation from below and distribution of consecrated water from above were united through the fairly modern technology of duplication, in other words, in the form of leaflets, the rituals were transformed into reality as a grandiose universe.

Consequently, the rituals of 1993 had collected rather excessive funds from contributions by individuals and organizations. Considering this fact, it is possible to estimate that the level of approval and a sense of participation in the rites were substantially high. On the other hand, however, it is hard to deny an ostentatious display of greed drenched in vanity, which could be seen through the purchase of private cars and homes as well as by the use of expensive clothes in 1990’s Bali, all of which were accumulated wealth from tourism. As a matter of fact, the names of donors and the amount of contributions were published in newspapers and the way the amount surged as the dates drew nearer to rituals was an indication that the large-scale rituals were a new site of showing off one’s conspicuous consumption and prestige. Making some donations to the rituals at Besakih temple had turned into a new means of “being ostentatious.”

On the other hand, since individual participation in the rituals was realized through the distribution of consecrated water via villages, it also brought to light the existence of those who couldn’t take part in the rites. Those born in and commuting to schools and working in Denpasar, the capital city of Bali province. Since their relationships with their parents’ villages have already become tenuous, they could not participate in the village-based rituals. It was a Hindu framework, which could accommodate such people including globally expanded religious Hindu groups such as Saibaba and Hare Krishna.

Such religious bodies would sharply criticize the Hinduism defined by Parisada, for being dependent on the community of Bali as well as binding people to authority, offerings and androcentrism. In contrast, these organizations held regular gatherings to discuss their matters and had been helping each other in their daily lives. As the voices of those born in Denpasar had become a large number to the extent that they couldn’t be ignored any more, Parisada had no choice but to acknowledge their existence as schools of Hindu (Bernafaskan Hindu). This was one of the triggers leading to their fragmentation, which will be mentioned later.

Saibaba’s Meeting Place in Denpasar

Representative Institutions of Minority Religions

The religious majority in Indonesia are Muslims, while Hindus are the minority who account for less than 10 percent of the population. The government has established its own system to authorize religions to handle the situation, in which religious minorities exist apart from the dominant majority. As a central government office, they have set up a Ministry of Religious Affairs to designate the official religions (agama) and to distinguish them from other religious practices regarded as faiths (kepercayaan), while approving various rights given to the official ones, such as the right of education at schools. It is a well-known fact that the system originated from the Ministry of Religious Affairs which had been established during the Japanese military regime period with an aim of pacifying in Muslims.

Parisada Headquarters

Hinduism was authorized as an official religion in 1958. After a long period of negotiation between the Bali government and the Ministry of Religious Affairs, the provincial government finally received official recognition for Hinduism. In the following year, Parisada was established as a representative institution for Hinduism in Indonesia. For the Balinese, it was an achievement of their long-held dreams. Not only religious people, but also politicians and intellectuals of the province came together under Parisada.

Acquiring official recognition meant that their activities across Indonesia were admitted. As they have expanded, there is no province at present, that doesn’t have a branch of Parisada, excluding the province of Aceh. With the exception of Bali, where Hindus are a majority, the religion is a minority in other parts of the country. Not only in terms of its institutional acknowledgement, but also in considering their protection from the surrounding Muslim populations, the existence of Parisada in regions outside Bali is significant for Hindus.

Schism or Historical Moment of Hinduism in Indonesia

At the turn of the 21st century, Parisada fragmented in Bali. In retrospect, it could be said that the split was inevitable, because of a head-on confrontation within the institution of Parisada, between the Balicentrists, who regarded rituals and practices in Bali to be essential to Hinduism in Indonesia, and the faith-centrists, who believed in the quintessence of the faith to be providing support for each person in their daily life and maintained this idea under the banner of democratization of Hinduism.

Since the 1980s, indications had begun to surface. In 1984, they were trying to form a nationwide mass organization under Parisada, however, they failed, due to the secession of Wayan Sudhirta and others. Thus, the mass organization first split. Wayan Sudhirta was the very person, who was later setting up a group, calling themselves Pemuda Hindu (Youth Fighter of Hindu), whose operational center in Denpasar turned into a base for the movements of the faith-centrists. In 2004, he ran in the provincial assembly election and made a summary of his public pledge in a leaflet. At first, at a conference called Mahasabha, a gathering of representatives of the branches across the nation was convened in 1986, which was then followed by Lokasabha, the provincial assembly of Bali. This was a prelude to the splitting of the Bali branch off from the totality of Parisada.

In 1991, after the 6th general meeting, those who had been unhappy with Bali-centrism organized the Forum Cendekiawan Hindu Indonesia and began to actively discuss the ideal of Hinduism as a faith. Then, after going through the Asian currency crisis in 1997 and the fall of Suharto regime in 1998, the breakup was conclusive since some members of Parisada Bali, leaning toward Bali-centrism, walked out of the integral Parisada in 2001. Thus, the resolution of the 8th general meeting was dismissed at a subsequent local conference in Bali.

People centered around Denpasar assembled under the movement to promote the democratization of Hinduism. Those included Pemuda Hindu at the center, along with groups of “shared origins” (groups based upon the idea of sharing an ancestral origin of birth. Those with their own temples, ceremonies and priests.) as well as members of Saibaba and Hare Krishna, mentioned above. The members of the groups of shared origins criticized the Bali-centrists for being privileged in two ways. They argued that the Bali-centrists based in Ubud were actually collaborators to colonial rule with some privileges granted by the colonial government, while at the same time, they were bowing to the Suharto regime to monopolize the benefits of tourism. Unlike theirs, priests belonging to groups of shared origin could not participate in the rituals at Besakih temple, so they insisted that such a fact be democratized and the priests of all kind of groups should be allowed to take part in rites. People centered around Denpasar Parisada Headquarters Center for Southeast Asian Studies Kyoto University 045 claimed they were also the Hindus and demanded voting rights in Parisada, which had not been accredited to them. As the resolution of the 8th general meeting had accepted these claims, Parisada Bali did not approve them.

It is possible to say that ritualism versus fideism is a universal composition of conflict at the heart of any religion. In the case of Bali, there is ritualism on one hand, rooted in village life and fideism on the other, accommodated through globally expanded religious activities. Furthermore, there were criticisms from a decolonialized perspective and accusations against monopolizing self-interests dependent upon the centralized administrative system. Hinduism has turned into a framework, under which respective discrete agents in strained relations would develop their own claims. In 1993, just before the fall of the Suharto regime, they barely managed to carry out the grand rituals of Besakih temple. Yet, after the collapse of the regime, the tension was explicitly exposed and as it was irretrievable, the representative institution of Hinduism, which was meant to protect the minority, split. Materials here shed light on the very historical moment in which Hinduism in Indonesia finds itself located.

References

Below are the materials on Hinduism in Indonesia given to CSEAS, including manuals of rituals at Besakih temple and proceedings of Parisada et al.

- Piodalan Ekadasa Warsa Parisada Hindu Dharma, 1959-1970: om dirghayur astu H. U. T. Ke-XI, Denpasar. Denpasar: Parisada Hindu Dharma, 1970. (Call No. IV In/3/1137)

- Seminar Tampaksiring tgl. 30 Djuni s/d 5 Djuli 1968. Kebajoranbaru: DPP. AMHI & Jajasan Dharma Dutta Dhana, 1968. (IV In/3/1138)

- Sambutan dan Hasil Keputusan Sabha (Kongres) II: Parisada Hindu Dharma Seluruh Indonesia, Tanggal 2 s/d 5 Desember 1969 di Denpasar - Bali. Denpasar: Parisada Hindu Dharma Kabupaten Badung, 1970. (IV In/3/1139)

- Parisada Hindu Dharma. Sekretariat. Sedjarah Parisada Hindu Dharma. Bag.: Penjalur-Penerbitan P.H.D. Pusat, 1970. (IV In/3/1140)

- Pesamuhan agung Parisada Hindu Dharma Pusat: 21 s/d. 24 Pebruari 1971 di Jogjakarta. Parisada Hindu Dharma, 1971. (IV In/3/1141)

- Hasil-hasil Maha Sabha Ke I s/d Ke III 1964. 1968. 1973 di Denpasar. Parisada Hindu Dharma, 1973. (IV In/3/1142)

- Om Swastyastu: Hasil-hasil Maha Sabha Ke III Parisada Hindu Dharma Seluruh Indonesia, Tgl. 27 s/d 29 Desember 1973 di Denpasar-Bali. Denpasar: Parisada Hindu Dharma Pusat, 1973.(IV In/3/1143)

- Hasil-hasil Maha Sabha IV Parisada Hindu Dharma se Indonesia, 24 s/d 27 Septemper 1980 di Denpasar Bali. Reprint. Originally published: Keputusan dan Ketetapan Maha Sabha IV Parisada Hindu Dharma se Indonesia, 1980. (IV In/3/1144)

- Hasil-hasil Maha Sabha IV Parisada Hindu Dharma se Indonesia, 24 s/d 27 Septemper 1980 di Denpasar Bali. Reprint.Originally published: Sambutan: Amanat dan Pengarahan, 1980. (IV In/3/1145)

- Laporan Pertanggung Jawaban Parisada Hindu Dharma Pusat Dalam Maha Sabha IV: pada tanggal 24 s/d 27 september 1980 di denpasar. Parisada Hindu Dharma Pusat, 1980. (IV In/3/1146)

- Himpunan keputusan Seminar Kesatuan Tafsir Terhadap Aspek- Aspek Agama Hindu I-IX. Denpasar: Parisada Hindu Dharma Pusat, 1983. (IV In/3/1147)

- Ketetapan/keputusan Pesamuhan Agung Parisada Hindu Dharma, Tanggal 24 s/d 27 april 1984 di Denpasar. Denpasar: Parisada Hindu Dharma Pusat, 1984. (IV In/3/1148)

- Keputusan/ketetapan Maha Sabha V Parisada Hindu Dharma se Indonesia, Tanggal 24 s/d 27 Pebruari 1986 Di Denpasar. 1986. (IV In/3/1149)

- Ketetapan/keputusan Pesamuhan Agung Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia, tahun 1987,1988, 1990. Denpasar: Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia Pusat, 1990. (IV In/3/1150)

- Himpunan Keputusan Seminar Kesatuan Tafsir Terhadap Aspek-Aspek Agama Hindu, I-XV. Proyek Penerbitan Buku- Buku Agama Pemda Tingkat I Bali, 1990. (IV In/3/1151)

- Keputusan dan ketetapan Maha Sabha VI: Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia, Tanggal 9-14 september 1991 Di Jakarta. Jakarta Pusat: Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia Pusat, 1991. (IV In/3/1152)

- Keputusan dan ketetapan Maha Sabha VI: Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia, Tanggal 9-14 september 1991 Di Jakarta. Jakarta Pusat: Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia Pusat, 1991. (IV In/3/1152a)

- Lokasabha II: Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia Propinsi Bali. Denpasar Bali: Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia, 1991. (IV In/3/1153)

- Guide book: Mahasabha I (the 1st general assembly) and the 5th Asean Hindu youth exchange programme Asean Hindu youth council: Bali, Indonesia, 15th to 17th nov., 1996. Jakarta: Ganeca, 1996. (IV In/3/1154)

- Perhimpunan Pemuda Hindu Indonesia (Peradah Indonesia). Hasil-hasil Mahasabha VI. Jakarta: Dewan Pimpinan Nasional Peradah Indonesia, 2003. (IV In/3/1155)

- Perhimpunan Pemuda Hindu Indonesia (Peradah Indonesia). Hasil-hasil Mahasabha VI. Jakarta: Dewan Pimpinan Nasional Peradah Indonesia, 2003. (IV In/3/1155a)

- Hasil-hasil Maha Sabha IX Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia. [Jakarta]: Taman Mini Indonesia Indah, 2006. (IV In/3/1156)

- Upacara tawur panca wali krama tgl.10 april 1978 di Pura Agung Besakih. Bali: Panitia Pelaksana Karya Panca Wali Krama, Betara Turun Kabeh dan Eka Dasa Rudra, 1978. (IV In/3/1157)

- Penjelasan tentang Karya Eka Dasa Rudra di Pura Besakih. Bali Denpasar: Kantor Wilayah Deppen Prop., 1979. (IV In/3/1158)

- Pura Besakih. Dati i Bali: Dinas Kebudayaan Propinsi, 1987.(IV In/3/1159)

- Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi: Pura Besakih. Dati i Bali: Dinas Kebudayaan Propinsi, 1988. (IV In/3/1160)

- Rencana induk pembinaan dan pengembangan Pura Besakih. Bali: Dwipa, 19--?. (IV In/3/1161)

- Tim Penyusun. “Upacara pañ cawalikrama di Pura Agung Besakih.” [Proyek Penerbitan Buku-Buku Agama], 1990. (IV In/3/1162)

- Drs. Nyoman Putra Suarjana, Iwayan Artha Dipa, sh. Pura pasar agung besakih kahyangan jagat (Gunung agung). Amlapura: Pantia Pembangunan Pura Pasar Agung Besakih, 1992. (IV In/3/1163)

- Yasa Kerti Umat Hindu Dalam Rangka Menyongsong Kerya CSEAS NEWSLETTER No. 77 046 Agung Tri Bhuwana, Candi Narmada, Panca Wali Krama Ring Danu dan Bhatara Turun Kabeh Tahun 1993. Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia Pusat, 1992. (IV In/3/1164)

- Karya agung candi narmada, panca walikrama ring sagara danu, tribhwana dan bhatara turun kabeh pura agung Besakih: ngurah oka supartha. Panitia Pelaksana Karya Agung Candi Narmada, Panca Walikrama Ring Sagara Danu, Tribhwana dan Bhatara Turun Kabeh, Pura Agung Besakih, 1993. (IV In/3/1165)

- Karya agung candi narmada, panca walikrama ring sagara danu, tribhwana dan bhatara turun kabeh pura agung Besakih: ngurah oka supartha. Panitia Pelaksana Karya Agung Candi Narmada, Panca Walikrama Ring Sagara Danu, Tribhwana dan Bhatara Turun Kabeh, Pura Agung Besakih, 1993. (IV In/3/1165a)

- Palihan Upakara: karya agung tri bhuwana, candi narmada, panca wali krama ring danu miwah bhatara turun kabeh. Tahun: Panitia Karya Agung Tri Bhuwana, Candi Narmada, Panca Wali Krama Ring Danu Miwah Bhatara Turun Kabeh, 1993. (IV In/3/1166)

- Tjokorda Raka Krisnu. Yasa kerti umat hindu menyongsong karya agung candi narmada, nyegjegang bhatri danu, tri bhuwana dan bhatara turun kabeh. Tahun: Dipersembahkan Dalam Rangka Persiapan Karya Agung Candi Narmada, Myegjegang Bhatari Danu, Tri Bhuwana Dan Bhatara Turun Kabeh, 1993. (IV In/3/1168)

- DPD Tk. I Bali Peradah Indonesia (Perhimpunan Pemuda Hindu Indonesia). Gunung Agung, Pura Agung Besakih, dan kita. DPD Tk. I Bali Peradah Indonesia, 1993. (IV In/3/1169)

- DPD Tk. I Bali Peradah Indonesia (Perhimpunan Pemuda Hindu Indonesia). Gunung Agung, Pura Agung Besakih, dan kita. DPD Tk. I Bali Peradah Indonesia, 1993. (IV In/3/1169a)

- Hasil Paruman Sulinggih Tingkat Propinsi, Yahun 1994/1995. Proyek Bimbingan dan Penyuluhan Kehidupan Beragama Tersebar di 9(sembilan) dati II, TH.1994/1995. (IV In/3/1170)

- Ida Bagus Gede Agastia. Eka Dasa Rudra, Eka Bhuwana. Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia Pusat, 1996. (IV In/3/1172)

- Palihan Indik Upakara Labuh Gentuh Panca Bali Krama Miwah Bhatara Turun Kabeh Pura Agung Besakih, Isaka Warsa: 1920; buku 1. Panitia Pelaksana Karya Agung Panca Bali Krama dan Bhatara Turun Kabeh Pura Agung Besakih, 1999. (IV In/3/1173)

- Panca Bali Krama: Pura Agung Besakih. Baliethnic, 1999. (IV In/3/1174)

- Jro Mangku Made Pinda. Geguritan Pura Agung Besakih: lan indik nangkilang Dewa Hyang. Besakih: [Jro Mangku Made Pinda], 2003. (IV In/3/1175)

- Menjadi pelayan umat. Denpasar: Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia Propinsi Bali, 20--? (IV In/3/1176)

- Pura basukian puseh jagat: pemugaran, pamelaspas dan ngenteg linggih 2002-2004. Panitia Pemugaran dan Pantia Karya Ngenteg Linggih, 2004. (IV In/3/1177)

- Kahyangan jagat pura samuantiga: Bedulu, Blahbatuh, Gianyar. Panitia Karya Padudusan Agung Pura Samuantiga, 2004. (IV In/3/1178)

- Keputusan/Ketentuan pasamuhan agung III maha semaya warga pande propinsi Bali: tanggal 10 Juni 2001 di wantilan sri kesari warmadewa mandapa pura agung Besakih. Denpasar: Maha semaya warga pande Propinsi Bali, 2001. (IV In/3/1179)

- Karya pemarisudha karipubhaya tawur agung, tawur gentuh lan pekelem di desa adat kuta, badung, Bali. Propinsi Bali: Panitia Pemarisudha Karipubhaya Tawuragung, Tawur Gentuh Lan Pakelem, 2002. (IV In/3/1180)

- Institut Hindu Dharma: Buku Pedoman 1984/1985. Denpasar: Kampus Tembau Penatih, 1985. (IV In/3/1181)

- Kantor Agama Propinsi Bali Denpasar. Tri-sandhya. Denpasar: Bhuvana Saraswati, 19--?. (IV In/3/1182)

- Upadeśa tentang ajaran-ajaran agama Hindu. Surabaya: Penerbit Pa¯ramita, 2001. (IV In/3/1183)