One of the fundamental religious obligations of Islam, along with prayer, fasting, and pilgrimage is almsgiving (zakat). This ‘pillar’ of the Faith (arkān al-Islām) is mentioned more than 30 times in the Qur'an, often in direct conjunction with prayer. Zakat is, moreover, the only of the pillars involving material transaction. It has traditionally been understood as both a mechanism for communal benefit in which the rich give alms to those less fortunate among the community, as well as a personal religious duty (Feener & Wu 2020: 1-3). Modern state systems have institutionalized the practice in many counties with the establishment of zakat management organizations with modern systems for the collection, management, and distribution of funds (Salim 2008; Fauzia 2013). In Indonesia, as elsewhere, Muslim scholars and NGOs have advanced a re-conceptualization of zakat, shifting from an emphasis on individual act to social obligation (Retsikas 2014: 345). Researchers have noted that historic practices range from face-to-face transactions between givers and receivers to taxes enforced by different Islamic polities (Bashear 1993: 99-108, Singer 2008: 47-48, Schaeublin 2019: 129).

Brief history of zakat management organizations in Indonesia

Over the past half century there has been a growing consensus in Indonesia that zakat, which was traditionally an individual practice, should be managed by a centralized, professional, and transparent organization. Since 1968, following the establishment of the first provincial level zakat management organization in Jakarta, many provinces decided to establish public zakat management organizations at the provincial level. Throughout the 1970s, many, including the Indonesian Ulama Council (Majelis Ulama Indonesia/MUI), have argued that the state should create a highly transparent and professional organization with compulsory zakat collection. Soon after the democratization in 1998, Article 23 of the Zakat Management Law was passed in 1999. Under the regime of President Abdurrahman Wahid, the state-run Zakat Management Body, BAZNAS (Badan Amil Zakat Nasional) was established in 2001 to centralize the management of zakat and supervise provincial-level zakat management organizations and private zakat management organizations (Lembaga Amil Zakat/LAZ). With these developments, the Indonesian legal system has come to incorporate zakat as a formal mechanism for wealth redistribution mechanism administered by the state. However, although the legal framework aims to centralize zakat collection and distribution there remains opposition to the idea from a number of individual religious leaders (kyai, ulama, and imams), and institutions including NGOs, mosque associations, private zakat management organizations, and provincial zakat management bodies in Aceh and Jakarta. Indonesia is therefore a region of complex and mixed forms of zakat practice, reflecting the amalgamation of diverse ideological currents and competing institutional actors in the country.

The new practice of using zakat as a loan

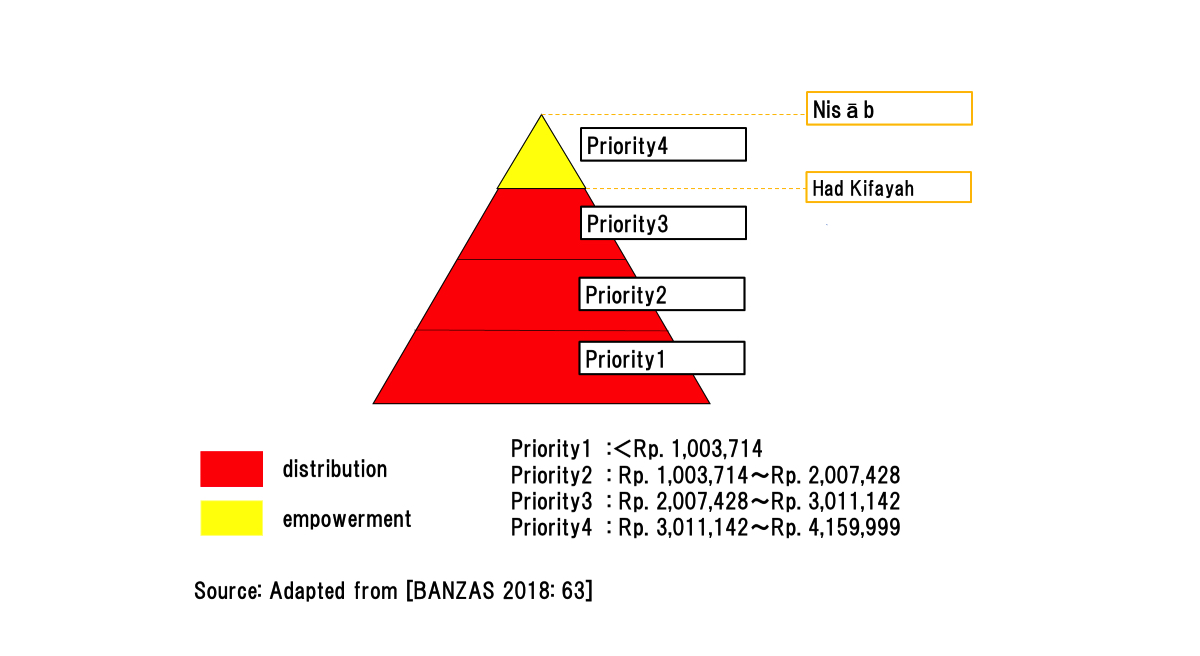

Based on Islamic jurisprudence, there are eight categories of eligibility for zakat (asnāf), the most important of which are the poor and needy (fakir, miskin). The formal administration of these qualitative conceptions of poverty have, however, proved a long-standing challenge. In recent years, one proposed solution has been the identification of a standard measure for an Islamic ‘poverty line’ (In. had kifayah / Ar. ḥadd al-kifāya; BAZNAS 2018: 4-18). Figure 1 presents the ‘recipient pyramid’ that was created by the research office of the Nasional Zakat Management Body (Pusat Kajian Strategis/ Puskas BAZNAS) to illustrate the levels of distribution in relation to their humanitarian and development priorities.

Photo 1 A customer pays back her debt in the office of a zakat management organization

(Photo by Mari Adachi, September 25, 2017)

Here we see how a poverty line is established to demarcate between traditional recipient category for the poor (fakir, miskin), and those eligible for ‘productive zakat’ distribution such as loans. First of all, from the perspective of the zakat administrators, one of the main subjects is how to optimize the impact of funds collected. Their discussions of this problem are often framed in terms of a dichotomy drawn between ‘consumptive’ and ‘productive’. This is not an established categorical distinction of classical Islamic jurisprudence, but rather a modern innovation designed to promote an effective deployment of the traditional to serve the needs of contemporary communities.

Consumptive zakat distribution here refers to expenditure to provide food, clothing, housing, transportation, health care, and education to address fundamental needs of recipients. Productive zakat (zakat produktif), on the other hand, is directed toward stimulating income generation among recipients who are evaluated as able to make efficient use of new capital. Productive zakat distribution thus aims to promote economic independence by providing financial assistance, job training and management supervision to recipients (See Photos 1 & 2). It is the concept of productive zakat that has provided the framework for imaging the use of donations to fund small interest-free loans, an idea that has been taken up eagerly by many Indonesia today (Nurzaman 2012: 5; Beik & Arsyianti 2016).

Photo 2: Street vendor (kaki lima) purchased with a loan received as zakat

(Photo by Mari Adachi, September 25, 2017)

In 1982 – after much deliberation – the Indonesian Ulama Council (MUI) issued a fatwa that legitimized new interpretations of some of the traditionally established categories used to define those who have a legitimate claim to receive zakat. This included a ruling that zakat funds intended for the poor and needy can be used for other social welfare activities, while that allocated for the support of ‘those who struggle in the Way of God’ (fisabilillah) can be distributed for purposes of serving the broader aims of public welfare (maslahah 'ammah) (BAZNAS 2011: 9-14). Following that, the Islamic Fiqh Academy (1986) also allowed the use of surplus zakat funds for income-generating investments. Interestingly, the Indonesian Zakat Act clearly stipulates that zakat can be used for productive activities to minimize poverty and improve the standard of living, but only after first addressing the basic needs of traditionally defined zakat recipients (mustahiq). (Art. 27.1-2). In this, Indonesia pioneered a new approach to the problem of prioritization in zakat distribution, one which to date has not yet been adopted by any other Muslim majority nation-state (Islamic Social Finance Report 2014: 58).

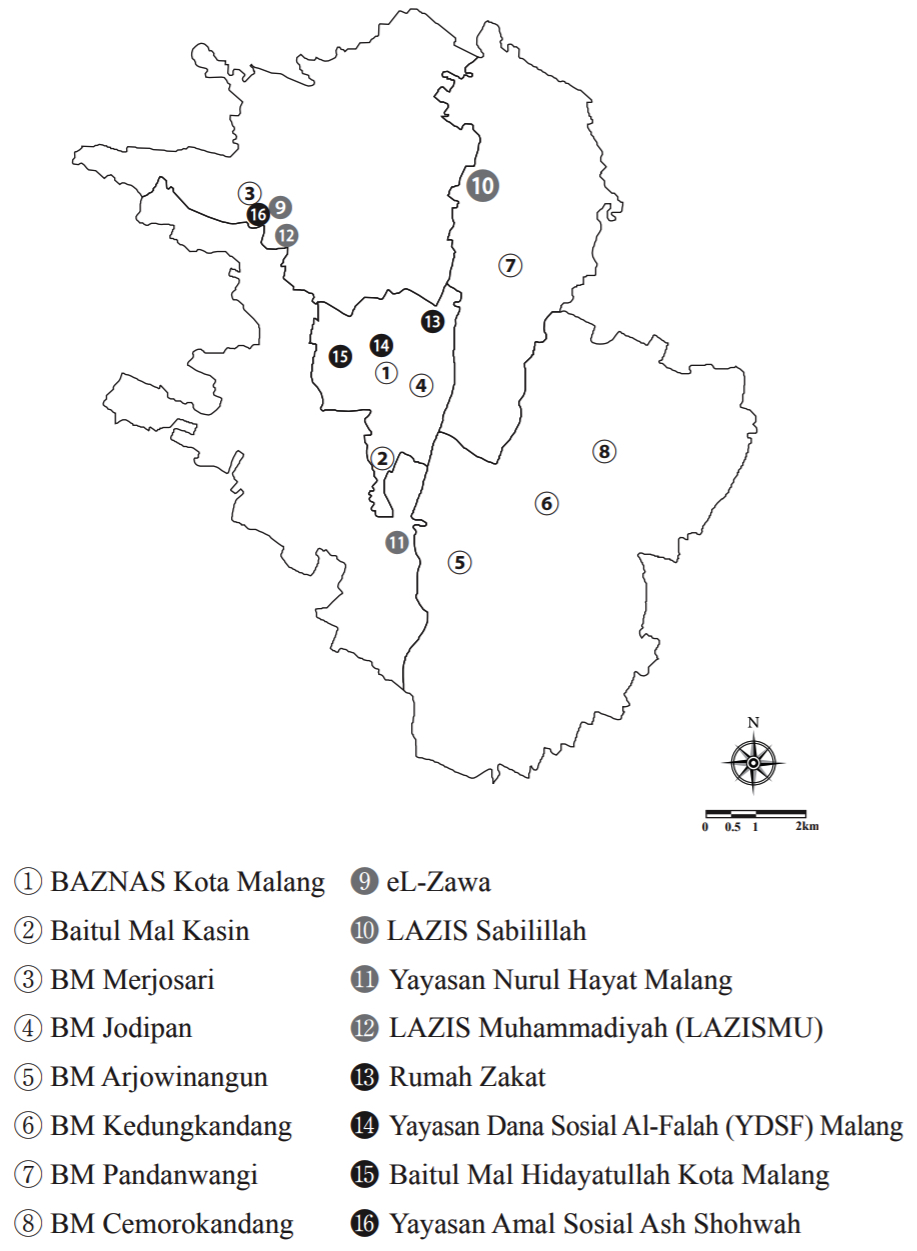

In order to delve into the actual operation of ‘productive zakat’, I conducted field work on zakat management organizations in Indonesia between November 2016 - October 2017. This took the form of an exploratory, descriptive survey conducted on zakat management organizations in the city of Malang, East Java. Data was collected from the questionnaires and interviews of the directors and managers of 16 zakat management organizations and 134 clients of its zakat loan in that city. The objective was not to criticize the working of modern organizations administering ‘productive zakat’ as an [heretical] ‘innovation’ (bid`a) in Islamic jurisprudence, but rather to explore these innovative practices of Muslims in contemporary Indonesia.

Fig. 1 Priority Pyramid of Zakat Recipient

The results of this research show that zakat management organizations promote funding to low priority customers (see Figure. 1). In addition to consumptive distribution, managers lend interest-free loans to low-income informal workers who cannot afford to give zakat. Of the productive program of zakat management organizations in Malang, ¾ of them ( ❾ ~ ⓬) collect money in the form of zakat on salary (zakat profesi, zakat penghasilan, or zakat gaji). Philanthropic organizations which do not apply a monthly mandatory withdrawal of 2.5% zakat ( ⓭ ~ ⓰) have no ‘productive zakat’ activities. They also do not distribute zakat in the form of microfinance (See the Figure. 2).

Fig. 2 Map of zakat management organizations in Malang city

In this map, the numbers ① ~ ⑧ represent Malang city brunch of BAZNAS and its distribution unit Baitul Mal (BM). Numbers ❾ ~ ⓬ denote private zakat organizations that have a productive zakat program. Numbers ⓭ ~ ⓰ denote private zakat organizations without a productive zakat program. The writer created this map with the interviews and pamphlets of each zakat management institution as a source.

Most previous studies have unilaterally understood zakat to be a form of charity, but this study shows that in Malang, zakat is also used as a tool of development. That model of zakat management aims to improve the economic prosperity of people in ways that transform them from zakat receivers (mustahiq) to zakat donors (muzakky). In this transformation, the zakat distribution managers and the recipients interact face to face. On the collection side, BAZNAS Kota Malang obtains zakat funds in partnership with the Malang Municipal Office1, but its distribution is delegated to the local Baitul Mal and its voluntary manager (See Photos 3 & 4). This helps to enhance the circulation of the funds within the city, and thus supports local economic development.

My work on the local implementation of these innovative approaches to the management of zakat funds presents a case that challenges established neoliberal perspectives that have tended to trivialize zakat as merely Islamic ‘charity’ or ‘philanthropy’ and often characterizes modern institutions for zakat administration as an aspect of Islamist agendas for capturing state power and centralizing control. Rather, these examples from Malang open a window onto a range of contemporary Indonesian experiments with models of productive zakat that present intervention strategies which retain aspects of traditional Islamic concerns for poverty alleviation, while also introducing new visions of religious giving channeled toward economic development and Muslim community empowerment.

Photo 3 The glossary shop owned by the voluntary manager of BM Kasin

(Photo by Mari Adachi, April 26, 2017)

Photo 4 A voluntary manager of BM Merjosari meets and greets a recipient during his patrol

(Photo by Mari Adachi, June 13, 2017)

References

- Badan Amil Zakat Nasional (BAZNAS). 2011. Himpunan Fatwa Zakat MUI: Kompilasi fatwa MUI tentang Masalah Zakat. Jakarta: BAZNAS.

- Badan Amil Zakat Nasional (BAZNAS). 2018. Himpunan Fatwa Zakat MUI: Kompilasi fatwa MUI tentang Masalah Zakat. Jakarta: BAZNAS.

- Bashear, S. 1993: “On the Origins and Development of the Meaning of Zakāt in Early Islam,” Arabica 40(1), pp. 84-113.

- Beik, Irfan Syauqi & Arsyianti, Laily Dwi.2016. “Measuring zakat impact on poverty and welfare using CIBEST Model,” Journal of Islamic Monetary Economics and Finance 1 (2), pp. 141-160.

- Fauzia, Amelia. 2013. Faith and the State: a History of Islamic Philanthropy in Indonesia. Leiden: Brill.

- Feener, R. Michael & Keping Wu. 2020. “The Ethics of Religious Giving in Asia,” Journal of Contemporary Religion 35 (1), pp. 1-12.

- Islamic Social Finance Report. 2014. IRTI and Thomson Reuters.

- Nurzaman, M. Soleh. 2012. “Zakat and Human Development: An Empirical Analysis on Poverty Alleviation in Jakarta, Indonesia” in 8th Conference on Islamic Economics and Finance, pp. 26.

- Retsikas, K. 2014. “Reconceptualising Zakat in Indonesia: Worship, Philanthropy and Rights”, Indonesia and the Malay World 42(124), pp. 337-357.

- Salim, A. 2008. The Shift in Zakat Practice in Indonesia: From Piety to an Islamic Socio-political-economic System. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

- Schaeublin, Emanuel. 2019 “Islam in Face-to-Face Interaction: Direct Zakat Giving in Nablus (Palestine),” Contemporary Levant 4(2), pp. 122-140.

- Singer, Amy. 2008. Charity in Islamic Societies. UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 23 Tahun 2011 tentang Pengelolaan Zakat.

Note

- 1 The Malang Municipal Administration deducts 2.5% of civil servant’s salary every month as zakat. The fund is collected, managed, and distributed by BAZNAS Kota Malang.