An undeniable issue for scholars interested in nineteenth-century Thai society is the limitation of available source material. Most available documentary sources are in the form of royal documents reflecting an official perspective, rather than those of most of the population. Trying to catch a glimpse of the lives of ordinary people in the past, social historians have used other sources such as newspapers, magazines, songs, films, novels, etc. In recent Thai historiography, one alternative source base that has been attracting attention is that of ‘cremation books’.

What is a cremation book? Those who are not familiar with Thai society might not immediately recognize or understand this genre. Cremation books (Nang Sue Ngan Sop) are books published and distributed at funerals that began to be published around the latter part of the 19th century. Their primary intended purpose of to honor and commemorate the deceased so that their good deeds and their lives will be remembered by their families and acquaintances. At first, only members of the royal family and noblemen could afford printing cremation books. Later, as the price of printing came down, ordinary people gradually joined this fashion and it becomes a part of Thai cremation ceremonies.

A cremation book can be divided into three main parts: 1) a biography of the deceased, 2) eulogies from families and friends, and 3) other documents. This last section may contain edifying material on the Buddha’s teachings (dhamma), excerpts from royal chronicles and other classical texts on the arts, medicine, botany, as well as Thai and Western recipes, self-improvement advice, etc. According to well established Buddhist teachings, such an impartation of knowledge can serve as one last good deed accruing merit to the deceased.

In addition to the actually biographies of the deceased presented in cremation books, another major aspect of their value as historical sources can be found in the selection of particular texts from the third section. The biographies often contain stories covering significant periods of the life of the deceased, generally including episodes from youth, and incidents from their education, career, and life after retirement. Customarily, family members are the ones who write a short biography for the deceased but sometimes families might choose to publish longer version of autobiographies or memoirs written by the deceased themselves. Regardless of their length, such stories depict how the deceased lived their lives and can provide fascinating details of changing lifestyles in modern Thailand.

The biographies also shed light on circles of friends/acquaintances and various kinds of relations especially, but not only, of public figures. These relations shown in both personal and official letters as well as eulogies. Thus, cremation books not only provide information about the deceased and their relatives, but also potentially shed some light on the on their social networks beyond their families.

Fig.1 Examples from the cremation books in the Charas Collection at the CSEAS Library at Kyoto University

The last sections of cremation books can also yield a wealth of information on the kinds of knowledge valued in the circles of the deceased – thus capturing snapshots of particular cultural moments in Thai history. Some material published in cremation books might no longer exist in other forms, and many of them are difficult to access, especially as they are drawn from rare books from the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries. From this, it should be clear that well beyond their initial purpose of memorializing the deceased, these books also benefit later generations as rich historical source material. Today, scholars and students of history have begun collecting cremation books. There is now a significant expansion of buying and selling cremation books of those who were famous in Thai society in particular. Among other institutions, Kyoto University currently owns one of the largest cremation book collections in the world: the Charas Collection (Fig. 1)1.

There are approximately 9,000 titles in the Charas Collection and 4,000 of which are cremation books. With such a great number of such publications, this library possesses the most wide-ranging cremation book collection outside Thailand. Several of them date back to the latter part of the nineteenth century to the reign of King Chulalongkorn, which also saw the emergence of the modern production of cremation books in Thailand.

I first used this collection in 2019 during my first year of Ph.D. studies at the Kyoto University Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies (ASAFAS). My thesis on the modernization of the Thai army as well as the lives and ideologies of Thai soldiers in the early twentieth century. In order to expand the scope of my research, I explored the new materials at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies Library, and came to recognize then the great potential of this source material for my research. I visit the library, I discovered an impressive number of cremation books from Charas Collection including cremation books of soldiers, mostly middle to high-ranking military officers. Many of them lived during the time of a great transition in the twentieth century, witnessing the collapse of an absolute monarchy and the rise of democracy after the 1932 Revolution (Fig. 2)2.

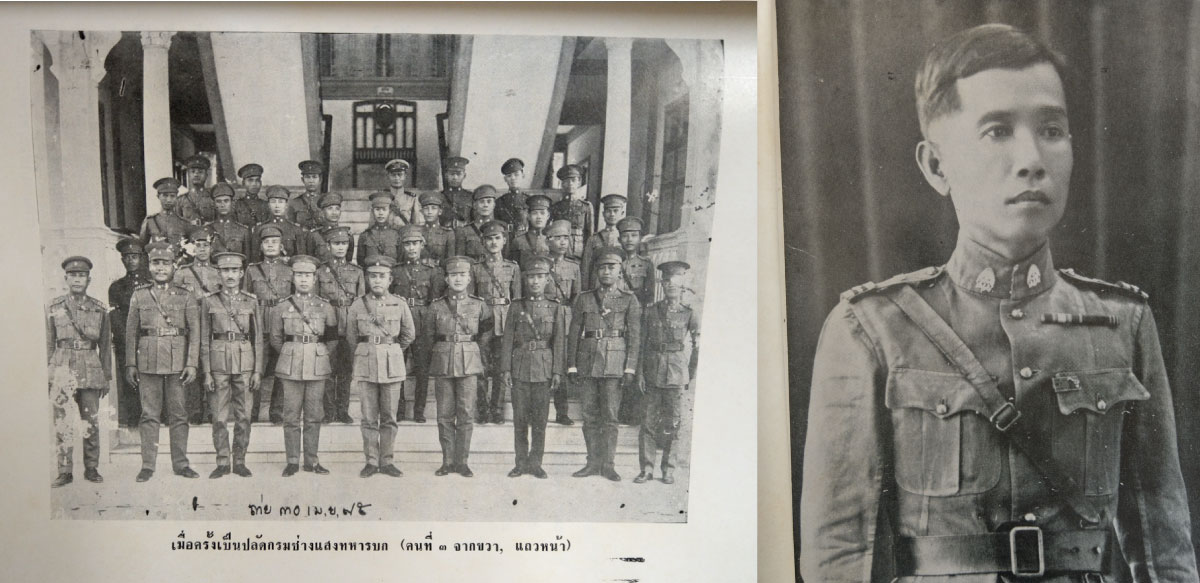

Fig.2 Images of Siamese soldiers: photos of Lieutenant Phra Akkhaniwut (Lamai Srichamorn) 2

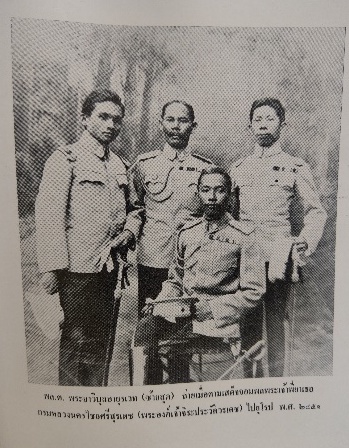

At the moment, the army played an important role as one of the leaders in the revolution. It was the first time the army stepped out of their barracks into the political sphere. Of course, since then coups and military interventions have become a familiar part of Thai politics. For my research, I explored these sources to understand the ideologies and perspectives of these soldiers’ understanding of society and political affairs(Fig. 3)3.

Fig.3 A photo of Prince Chirapravati, with an official from the Ministry of War and Siamese Army commissioned officers

I found some particularly interesting memoirs and autobiographies of those who graduated from cadet school and joined both the 1912 Soldiers’ Plot and the 1932 Revolution. The Charas Collection includes the cremation books of leading military officers such as Colonel Phraya Riithiakhaney (พันเอกพระยาฤทธิ์อัคเนย์), General Admiral Air Chief Marshal Mangkorn Phromyothee (พลเอก พลเรือเอก พลอากาศเอก มังกร พรหมโยธี), Lieutenant General Prayoon Pamornmontri (พลโท ประยูร ภมรมนตรี), General Luang Hansongkram (พลโท หลวงหาญสงคราม), Sub Lieutenant Rian Srichan (ร้อยตรีเหรียญ ศรีจันทร์).4

Their stories reflect their dissatisfaction with the injustice and inequality treatment in the army, particularly between royal members of the officers’ corps and non-royal military officers. Being royal meant better treatment and better opportunities to study at military academies abroad and were promoted to higher positions faster than those who were not born of noble families. Additionally, in terms of difficult political and economic crisis that happened at that time, these soldiers believed in their potentials to protect and to rule the country. They were smart, strong, and sensible. They were not mere soldiers but revealed themselves as leaders. Thus, they resolved to overthrow the absolute monarchy and situated themselves as a leader of democratic reform.

Another thing I discovered is autobiographies of those who participated in a rebellion of royalists who were against the 1932 Revolution and in response launched the Baworndech Rebellion in 1933. In contrast to those who involved in the 1932 Revolution, I found cremation books of Major General Luang Phlengsatharn (พลตรีหลวงแผลงสะท้าน), who flee to Saigon after the rebellion failed, and Captain Luang Sornchittiyothin (ร้อยเอกหลวงศรจิตติโยธิน).5 They both described their loyalty to the monarchy and never hesitated to protect the throne. Some soldiers did not write about this incident directly but their short biographies reflect how standing on the losing side affected their careers. Several of them resigned and many of them were indirectly forced to leave their positions in the army after the rebellion.

Through the sources presented by these cremation books I can see both sides of the story, from the perspectives of winners and losers. The winners claimed their victory and praised the democratic reform, on the contrary, the losers maintain their loyalty to the king. The different perspectives that can be accessed through these cremation books are crucial because they document diverse ideologies, perspectives, and feelings among soldiers in the army. It is true that the army attempted to implant the same ideology into soldiers’ minds through military training but there were other factors that shaped these soldiers in ways that resulted in considerable diversity of opinion among them.

Although these fascinating accounts reveal diverse aspects in the Thai army, like any other historical source there are also limitations on the use of cremation books. Because this type of books is for honoring the deceased, it inevitably depicts a positive side of their stories. Not all cremation books contain all the details we might expect or want. This is particularly the case for those who were not aristocrats, royal family members, or public figures. Some books have no details at all except a short list of what the deceased had done in the coruse of their lives. Yet, cremation books are still useful for social historians interested in various aspects of Thai society.

Those who are interested in Thai history should consult the Charas Collection at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies Library. One issue to be noted in using cremation books is that they are difficult to categorize because of the varied nature of their contexts. Thus, I would suggest starting with familiar names or famous figures. If you have more time, then you could browse the shelves and you might discover remarkable details from other volumes adjacent on the shelves. In addition to the Charas Collection, the CSEAS Library has gradually expanded the number of cremation books in their general collection, so that more cremation books are also now available and easy to access here in Kyoto.

Notes

- 1 Cremation Book of Major Phra Chamnankuruwit (Yam Phamornmontri) and Mrs.Chamnankuruwit (Annelly Phamornmomtri) (Bangkok: Sophonphiphatthanakorn, 1930); Cremation Book of Field Marshal Phraya Bodindechanochit (M.R.Arun Chatkun Na Krugthep) at the Royal Plaza 1922 (Bangkok: Sophonphiphatthanakorn, 1922).

- 2 The cremation of Lieutenant Phra Akkhaniwut (Lamai Srichamorn) at Somanatworawihan November 17, 1917. Akkhaniwutnusorn (Bangkok: Mahamakut Ratchawitthayalai, 1971).

- 3 Cremation Book of Major General Phraya Wibun-ayurawet (Sek Thammasarot) at Thepsirintharawat Temple, July 27, 1972 (Bangkok: Mongkonkanphim, 1972).

- 4 Cremation Book of Colonel Phraya Riithiakhaney at Thepsirintharawat Temple, May 25, 1967 (Bangkok,1967); Rian Ramluk. Cremation Book of Sub-lieutenant Rian Srichan at Makutkasattiyaram Temple, November 6, 1971 (Bangkok: Aksorn Thai, 1971); Cremation Book of Lieutenant-General Prayoon Pamornmontri at Phrasrimahathatworawihan Temple, November 25, 1982. (Bangkok: Bophitkanphim, 1982); Cremation Book of General Admiral Air Chief Marshal Mangkorn Phromyothee at Thepsirintharawat Temple, June 29 1966 (Bangkok: Krom Samphamit Press, 1966).

- 5 Ruengsun Cho Chang (Short stories of Cho Chang) Cremation Book of Major General Lung Phlaengsathan and Captain Sutthawit Anekamai (Bangkok: Arun Press, 1961): Cremation Book of Captain Luang Sorn Chitiyothin at Sommanat Temple, June 5, 1973 (Bangkok: Bamrungnukunkit, 1973).